October 31, 2022

Lula won

Barely. There is more to say on this, but it does not look to be over yet. The economy is in shambles after years of right-wing rule.

Imposed conditions

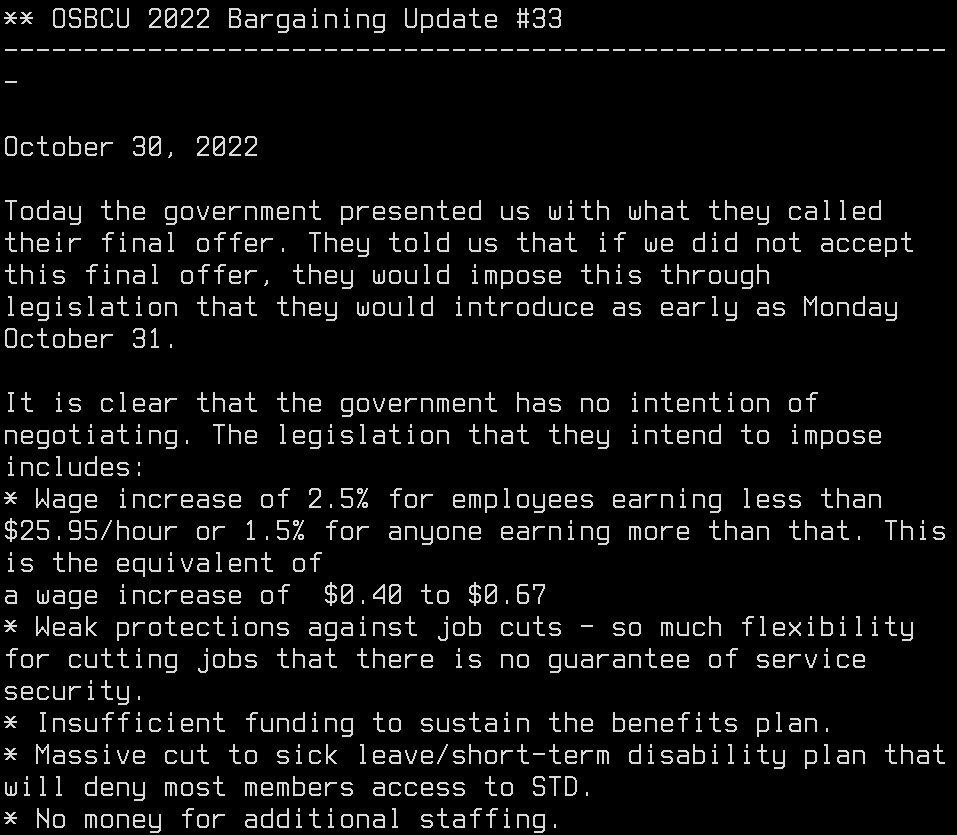

The bargaining arm of the CUPE's school board sector put out this last night after meeting with the province:

After the meeting, union president Laura Walton told reporters the province intends to use a bill to impose a four-year contract on the workers.

It is expected to be tabled today and include the terms laid out in Education Minister Stephen Lecce’s latest offer: 2.5 per cent annual wage increases for salary grids less than $43,000 and 1.5 per cent for all other salary grids.

That’s a slight increase from the government’s previous offer of two per cent for those earning less than $40,000 and 1.25 per cent otherwise. (Queen's Park Daily)

It seems clear to me that the government's plan all along was to impose conditions on school board workers and not engage in real bargaining. Bargaining is basically mechanical where the default is strike (or lockout) action if the employer (or the union) refuses to engage in bargaining.

The difference here is that the government is imposing conditions and ending the "strike" before it is even able to begin. This is a direct assault on the right to free collective bargaining.

The question remains how the union and the membership will respond. Workers tend to not respond well to imposed conditions.

Profitability, interest rates, and taxes

Here is a rather unlikely source for analysis on profitability and its "long-run" trend downwards. The Federal Reserve in the USA.

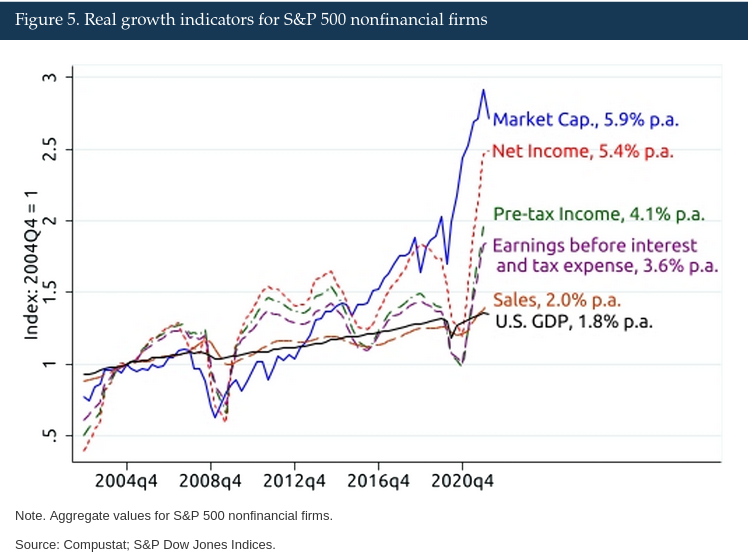

A paper, The coming long-run slowdown in corporate profit growth and stock returns, published at the end of September looked at profit rates in the financial sector and looked at why profit rates of publicly traded non-financial companies seemed rather high from the beginning of the 2000s to the end of 2020.

The analysis points directly to USA corporate tax rate reductions, artificially low interest rates, and low expenses (globalization of production to low-waged areas) for the profit supports.

The estimate is that at least 1.8% of yearly growth in corporate profits were due to the artificial factors of low interest rates, state-supported wage suppression, and reduced corporate taxation (what we refer to in the CPress Brief wholistically as "profit subsidies"):

The decline in the corporate tax rate in the USA fell from just over 30% in early 2000s to 15% in 2020. At the same time, interest rates continue to be pushed down by central banks to zero (or even below zero in Europe).

In other words, the relative decline in interest and tax expenses is responsible for a full one-third of all profit growth for S&P 500 nonfinancial firms over the past two decades (1.8 / 5.4 = 1/3). This is a very substantial contribution.

… for output produced within the U.S., growth in labor productivity—i.e., real output per hour worked—exceeded real wage growth since the mid-2000s.9 This means that, for a given cost of labor, firms were able to produce more output, which would also likely have contributed to the improvement in profit margins. (FR)

While not a surprise to any of us, it is a bit funny to see it in print so clearly from the research department of the USA's central bank.

The take-home from the paper is that there is no reason to think that growth in profitability will return easily because interest rates have to go up, taxes cannot be reduced any farther, and globalization has peaked in its ability to suppress wages.

The thing is that the way that profitability—at the macro level—can be returned is through wiping-out unprofitable production, increasing the supply of labour (increasing unemployment and immigration), and for companies to be forced to pay down their debts.

Say, through a recession caused by increased interest rates.

Taken all together, the above analysis implies that a reasonable forecast for the longer-run real growth rate of corporate profits is probably in the range of about 3 to 3.5 percent, but it might be even lower.

What does this imply for stock returns? Over the past two decades, the market capitalization of S&P 500 nonfinancial firms increased at a rate of almost 6 percent in real terms. (FR)

The implications of this are large, of course. Growth rates of financialized companies and financial markets are the cornerstone of the "modern" capitalist economy. Profitability of underlying companies are what financial markets are based on. They are also what economic growth is based on.

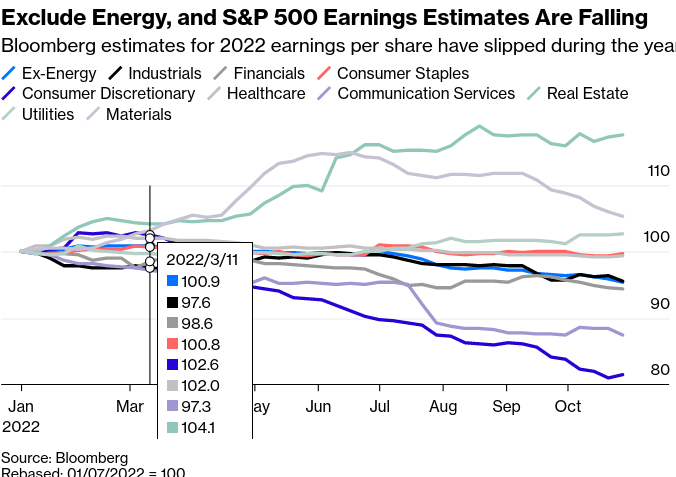

Or, at least that is how it is supposed to work. Unfortunately, it isn't working that way right now:

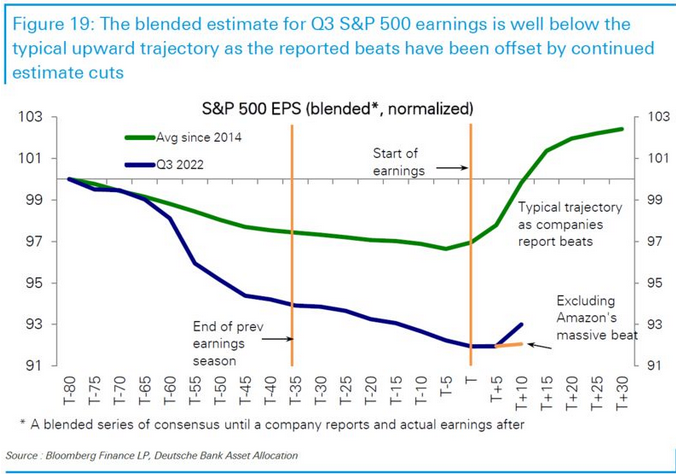

Earnings of companies are down, but not as far down as it seems investors had predicted. So, markets are not down as far as one might predict from all the data:

The unfortunate part is the whole thing is an extremely large bet on a "soft landing" of the global economy. If the bet goes the wrong way, things could go south very quickly.

In the medium term, what is worrying is that when clearly identified profitability crises happen, Capital pivots its policy demands to restore profits. The result historically has been anything from global wars to most recently decades of neoliberalism.

This is a far cry from just last year where over 130 countries signed a deal to increase taxes on the largest corporations:

OECD calculations that show governments could collect more than $150bn in additional taxes annually from the world’s largest corporates.

Something rather unlikely given the situation we are in.

Finally, it should be stated that artificially low interest rates are just a profit subsidy under the current policy frame. An unsustainable one at that. Higher interest rates is also bad(ish), but in the current situation it is likely precipitating the crisis before it is precipitated by itself—a result of profit subsidies. Without talking about everything else in the economy, talking about interest rates going up and down does not really mean much.

Central Bank's feeling the political pressure

The "markets" are expecting the central banks to not raise their interest rates as fast and maybe even reduce their rates in the short to medium term. These expectations come as the Federal Reserve meets this week to announce rates.

I say "expectations", but I think at this point we can just call them "hopes". Investors, politicians (weirdly of the centre-left and fascist variety), and some unions are all calling for central banks not to push the economy into recession to bring inflation down.

Morgan Stanley's Michael Wilson, who until recently was a prominent stock market bear. He pointed to recession indicators and said a pivot may happen "sooner rather than later."

Last week, Canada's central banker Macklem was accused of undermining the independence of the central bank by not increasing rates as fast as "expected". Some suggested he was even listening to the NDP (and the far-right) after Singh suggested there was "no merit" to rapid rate increases.

In Italy, the fascist government also demanded that rate-increasing central bankers not be so bold:

In the run-up to the ECB doubling its benchmark rate Thursday, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said such a decision would be “considered by many to be a rash choice, which runs the risk of impacting banking credit to families and businesses.”

That came after French President Emmanuel Macron and Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin expressed their own angst.

I refer back to my previous posts on why a simple answer to "should interest rates go up or down?" misses the point.