October 13, 2022

Private Digital in Health

The near silent privatization of public health (and other private) information has been an ongoing issue around the world. Most people are not aware of the magnitude of this as most people do not understand how databases and "online" services work.

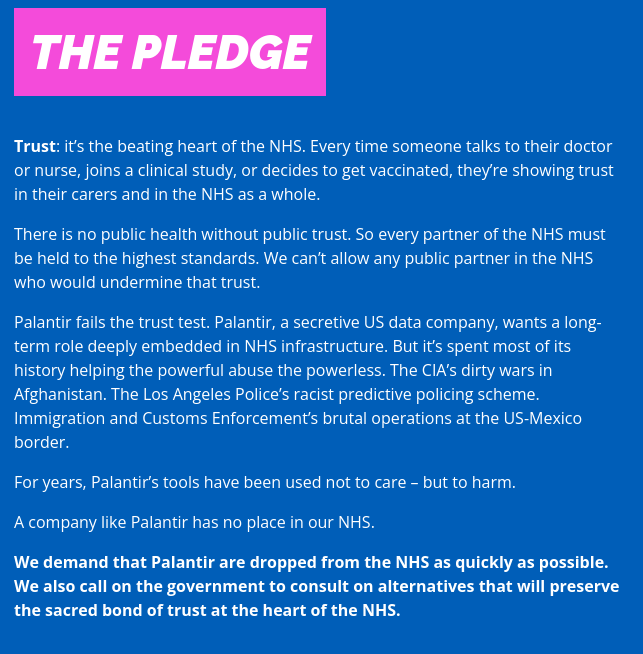

In the UK, the privatization of digital health records is being challenged by Foxglove, a little public interest legal clinic. Their current focus is the evil Palantir founded by Trump-loving Peter Thiel. This company has not just sucked-up UK health data during the drive of the NHS to modernize patient records and logistics, but it is now sucking-up all the competitors in that small marketplace.

According to Foxglove, it will soon become a monopoly of information technology provision in the NHS.

Palantir is a company that is almost exclusively dependent on government contracts to do what governments should be doing in house. Its revenue was $1.5B in 2021 and net income /negative/ $488M. How is this possible? It has the same "growth" model as many tech companies where they out-compete everything—including in-house resources—through debt driven acquisitions and running at a loss in the short-term. The long-term plan is to drive prices up when they have a monopoly.

- Foxglove's campaign is here. Called No Palantir, the campaign seeks to build public support for their lawsuits and educate the public on the commodification of health data.

Why should you care about the commodification of health data? Because once that data is commodified, it becomes a key part of a nexus of privatization of all future health services.

To understand this, you have to look at the way that future services are going to be tailored to individual patients. Everything from diagnostics to building new individually tailored drugs/treatments will be based on these new data sets. If the data sets are all privately owned, all services will be based on the renting of access to this data. This includes public interest health research and health outcomes.

The power of privatized health data cannot be overstated.

Core Inflation

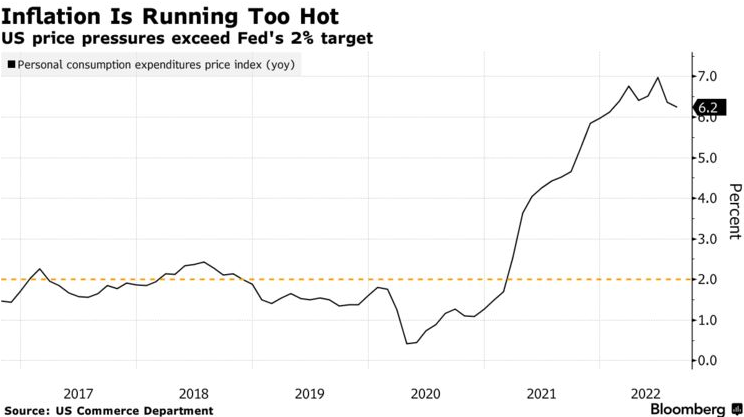

The number everyone will be talking about is "Core (Price) Inflation" this week, in contrast to "headline (price) inflation".

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the increase in the CPI last month was little changed from the 8.3 per cent annual rise recorded in August — and will increase pressure on the Federal Reserve to proceed with aggressive monetary tightening.

The core CPI measure, which strips out volatile energy and food costs, rose by 6.6 per cent on an annual basis last month, faster than the 6.3 per cent rate in August, a sign that underlying inflationary pressures were still accelerating. (FT)

There are many ways that we measure price increases. They all involve looking at a basket of goods, but depending on what is in that basket and who you exclude from counting, you can get all sorts of "inflation" numbers.

The key for working people is not the headline or core inflation number. We are interested in the lived experience of price increases as a percentage of our take-home pay.

The complex web of input prices that affect our ability to purchase things we need to survive is hard to understand. As energy prices go up, so does the cost of most things—but usually not right away. So, we are concerned about energy prices on the future costs.

However, the effects of the global climate, health, and economic crisis is the real issue we need to be paying attention to. As it gets harder to grow food, find healthy workers, and have jobs that pay it is the ability to buy that we really care about.

That measure the stress working people face making ends meet and the number of people in that high stress zone is what really matters.

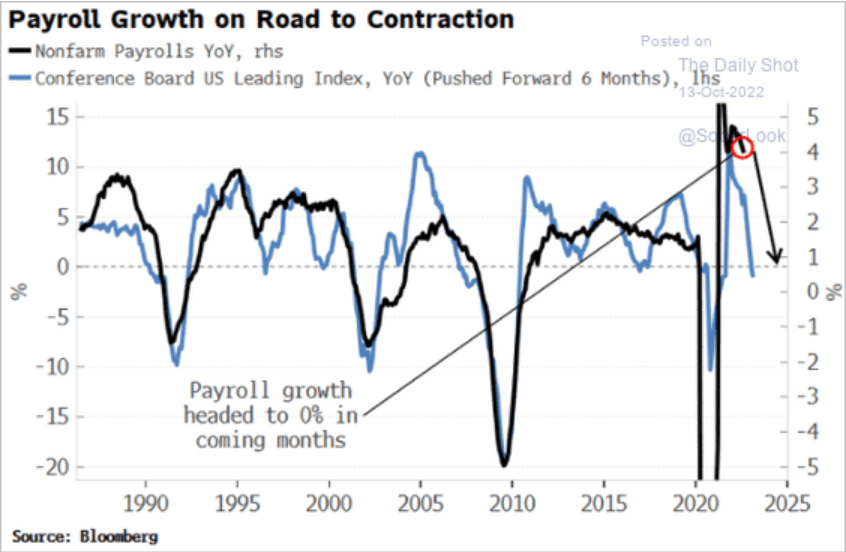

Global recessions mean jobs disappear

Recessions—especially global ones—are one part of this equation. And, it looks inevitable that we are heading there.

Part of the ability to pay for things is based on having a job that pays. If you don't have an income, it becomes almost moot how much things are.

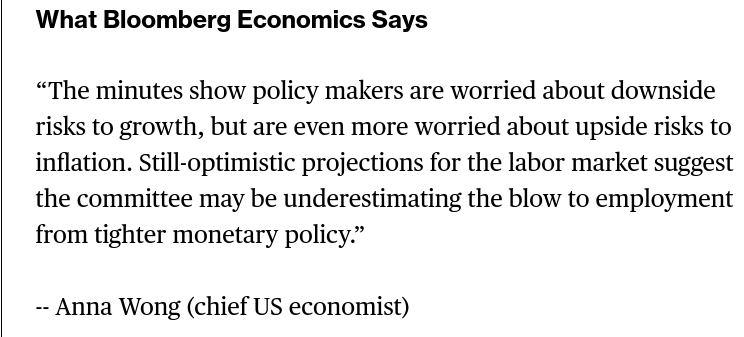

The central banks seem to be uninterested in this fact. They want to push as many workers out of work as is "needed to reduce inflation". This means recession, but also means millions of workers will be forced into poverty.

And all because orthodox liberal economists continue to lean on an outdated understanding of the economy. And, they are pushing harder on that recession pedal as they worry more about doing "too little about inflation" than they do about causing suffering of people.

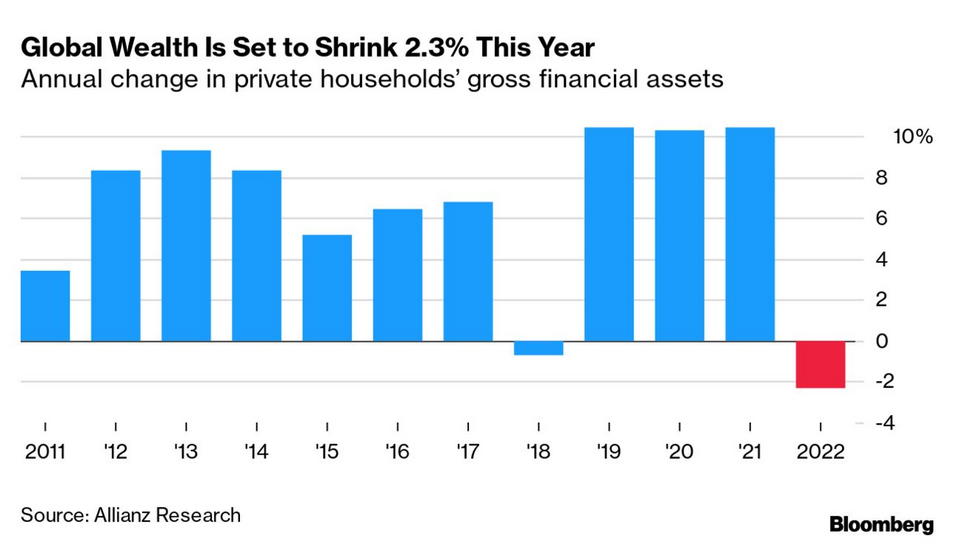

The whole mess is leading to a real decline in wealth.

Even the "affluent middle class" are going to have a tough time as growth in financial assets (including homes) are set to slow. This has a real impact on the perceived (real) wealth of affluent working people. You might think that this pushes workers into common cause, but history shows that the default is division.

“In contrast to the Great Financial Crisis, which was followed by a relatively swift turnaround — not least in asset markets — this time around the mid-term outlook, too, is rather bleak: The average growth of financial assets is expected to be at 4.6% until 2025, compared with 10.4% in the preceding three years,” the group said.

Most stock markets are very likely to end the year “in the red,” Allianz said, adding that it’s unclear whether recent interest in equities as an asset class will prevail in some parts of the world amid the subdued return prospects. (BN)

Additional interesting graphs of the economy

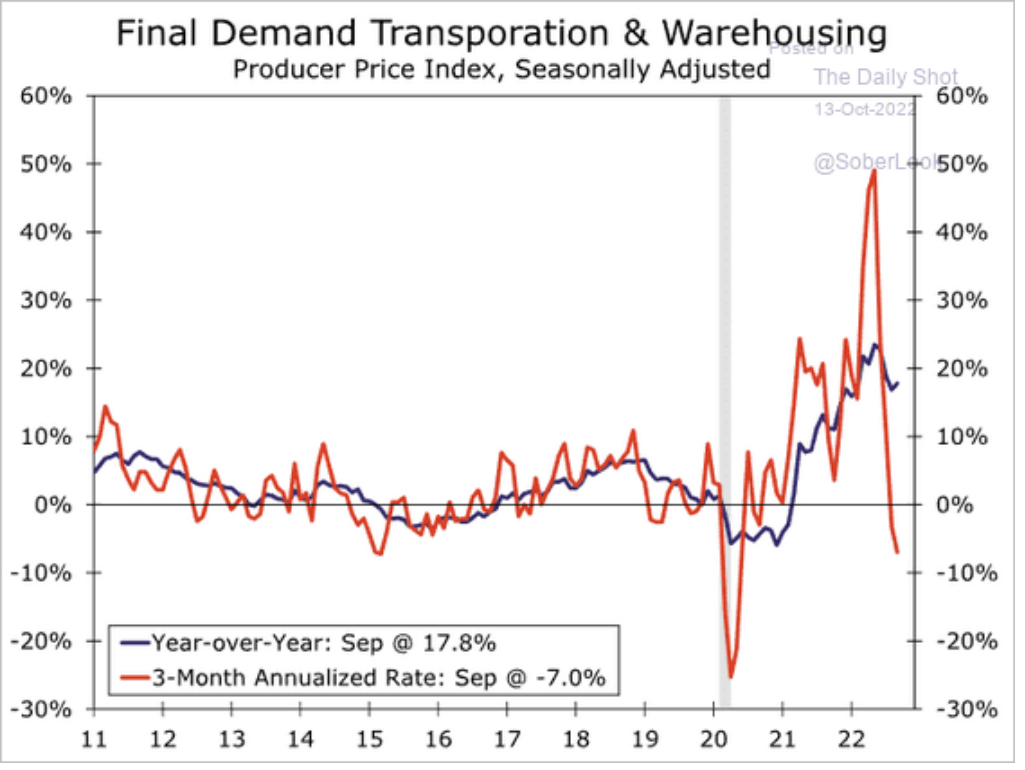

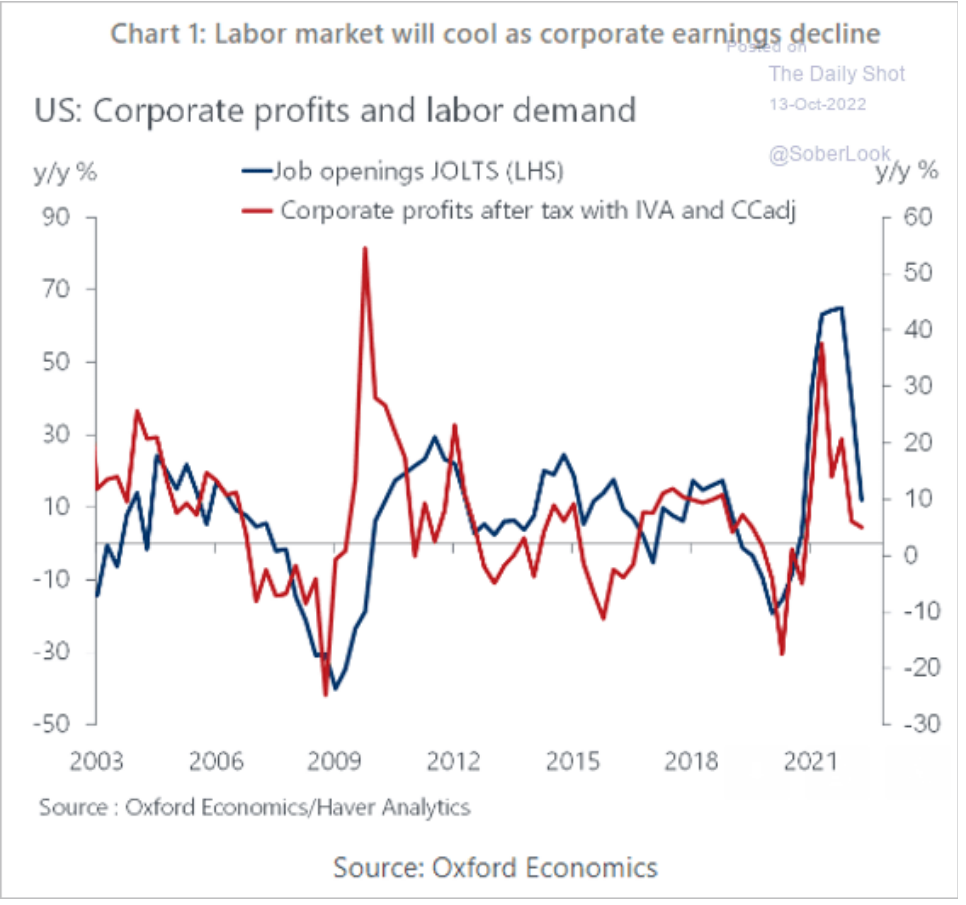

Tightness in the production market has collapsed in the USA, and profits will be reduced along with that.

Costs for warehousing goods is fluctuating, but the tenancy is down as production diminishes.

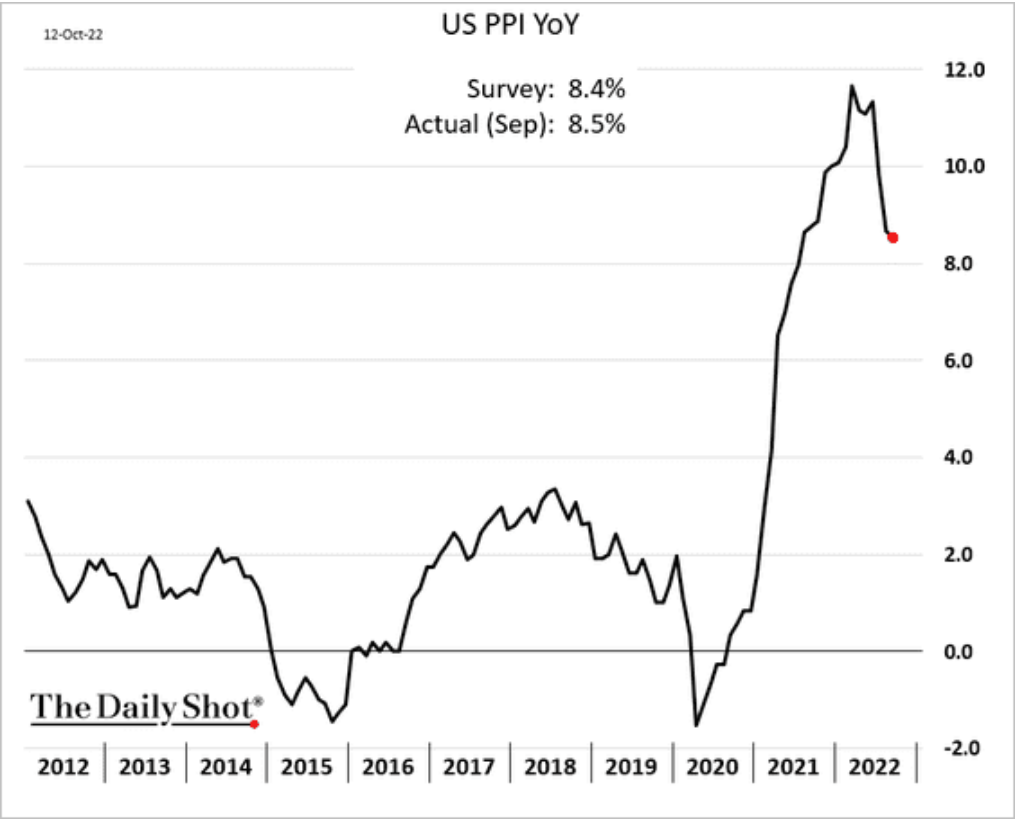

However, the cost increases for producing things remains elevated. Which means prices are not going to be coming down any time soon.

The short of it is that profits are going to be coming down for major producers in the US, so this argument will stop being effective for the centre-left soon. Another sign that there is "monopoly" situation driving prices/profits.

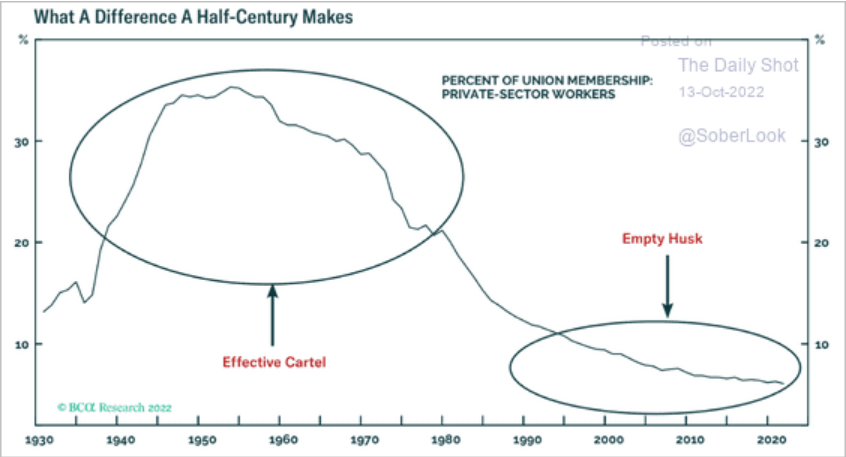

Wage-price spiral? Hardly. The Federal Reserve have admitted that there has been no wage-prices spiral, but still go on and on about the risk. Employment competition (and thus downward pressure on wages) is about to heat-up again in the USA even as wages have not even been close to inflation.