November 7, 2023

Deficits and spending

While we may have come through a period through and just after the pandemic where we were all Keynesian, it seems that we are headed to a period where no one wants to spend money.

Deficits are high, debt is pilling up, money and savings are running-out, and costs continue to go up and stay high.

The word "austerity" is being floated again, though the policy recommendations look more like direct cuts than simply a slowdown in growth.

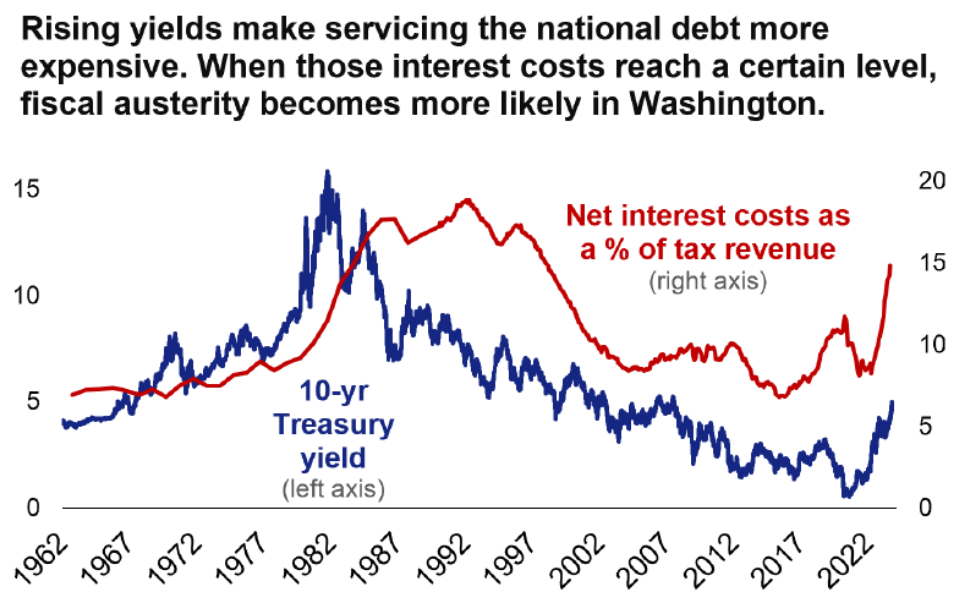

The price of debt is affected by both the interest the government pays on the debt and the price of the bond to get new debt. Here is an example from the USA and Auther's blog:

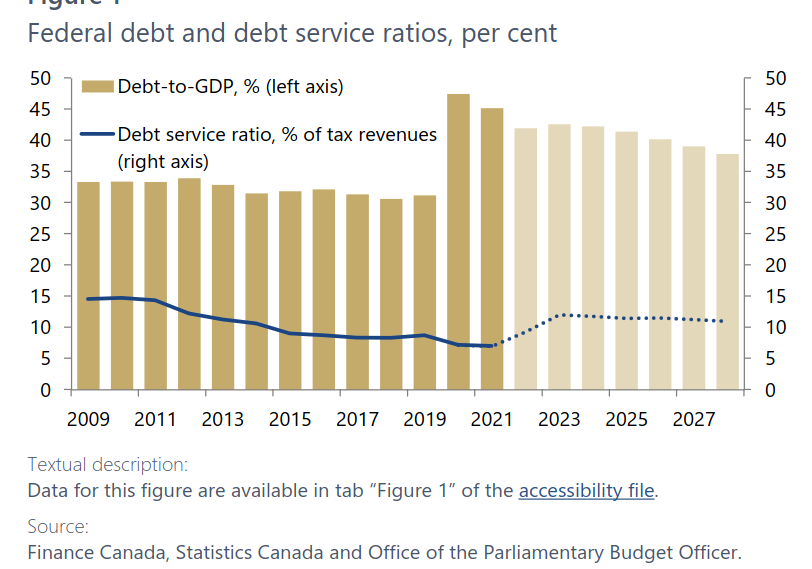

Canada has a similar problem:

PBO projects the debt service ratio (that is, public debt charges relative to tax revenues) under status quo policy will peak at 12.0 per cent in 2023-24 and then decline gradually to 11.0 per cent in 2028-29—well above its pre- pandemic low of 8.3 per cent in 2018-19.

Now, these numbers are hardly catastrophic for governments, but for neoclassical liberals (which includes Tories) any movement up of debt service numbers turns into an opportunity to say the word "cataclysm" while essentially demanding one.

The calls are already beginning in some of the policy circles that affect real things (i.e, not social media). This is partly because Corporate America also has a debt servicing cost issue.

WeWork filed for bankruptcy today, surprising no one. But, the story of WeWork is the story of many companies over the previous decade of low interest rates and hype machines working overtime. When interest rates are low two things happen:

- People think that they should borrow more money to buy things that they want.

- More money means more resources going into intricate and sophisticated communications that explain why taking on ridiculous amounts of debt is a great thing.

WeWork is a classic example of this where they continuously talked about how they were a software company when in reality they are a classic property re-leasing agent with a fancy website. Everyone now says that "everyone knew this already", but that cannot be the case. People didn't know, not even their investors, because they were taken in by the hype.

Same goes for many of these companies caught-up in the this bizarre world of no-value creation, debt driven, law avoiding Innovationism.

Governments too were taken-in and provided billions of dollars to subsidize these companies while reorganizing entire research and policy regimes to support private financial investments over needed productive ones.

MaRS is one classic example in Ontario where money was spent to subsidized failing "innovation" companies, but there are other more subtle changes.

The language and narrative used to talk about infrastructure and climate change investments coming from the infrastructure banks is trapped in the narrative. While it has shifted partly from "just give companies money" narrative of the early 2000s, it is still trapped in the idea that the private sector can borrow more money that government. "Governments cannot do it alone, they must combine with and subsidize private capital" is a refrain we hear all the time at from government Standing Committee witnesses.

Is it true? Kind of. We have given finance all our money on the promise that the market would deliver for us. Now, our policy people are confused that the money was not invested "properly". Instead of demanding our money back (in the form of public investments), our neoclassical policy branches are trying to figure-out ways we can incentivize private capital to invest properly.

The Canada Infrastructure Bank (and other like-minded organizations) are the manifestation of this program. They exist to invest 1/3rd of the up-front capital to get 2/3rds of highly subsidized money from the private sector. The subsidy isn't enough though, the program directs these investments through P3s which guarantee profits over the long-run (30-50 years) and increase overall costs to consumers. The worst part, though, is that the public lose control over the direction of investments over that 30 year period. So, we will be living with these policy mistakes for a generation or more.

The latest example I have been watching is the High Frequency Rail project of the federal Liberals. It is hard to call it a rail project, all the money so far has gone to not building rail and the timelines are so long before things start that it is likely that it will be shelved by the Tories if/when they get into power.

The one confusing part of this is that Canada is usually a follower of policies invented elsewhere. But, in the USA the government just gave $16B to Amtrak to repair and upgrade its infrastructure. Those projects will start now and are publicly financed through a variety of programs estimated to create 100K union jobs.

The Canadian HFR project has only created half a dozen high-paid executive positions with the promise of billions of subsidies. But, I guess that is kind of the point if your program is driven by corporate executive hype machines.