November 5, 2024

Climate change and politics

The National Farmers Union in the UK, long since taken over by large agro-businesses, has written that the inheritance tax is bad for farmers.

If the NFU's members were real farmers, they would be writing about something else.

Most family farms are no longer passed down through the generations to younger farmers. The land is leased to large-scale operators.

What does this have to do with climate change?

The narrative recounted by the NFU is based in the old-timey idea that farms are run by small-scale farm families, whose biggest issue is distribution of their food to market.

The reality is that the main issue facing UK farming is climate change, an issue which concerns their conservative political alliance so little that they barely address it.

Spain is nearly in political crisis after the floods in Valencia. Everyone is blaming politicians and the state for not telling the people of the town that the weather was going to get as bad as it did.

I find the reporting on this rather shocking.

While there were significant challenges with the emergency weather system, the emergency notification system, and evidence that government officials were reluctant to tell the population of the coming catastrophe, it isn't surprising.

We are living in a time where people refuse to believe how bad it is going to get over the next few decades. In fact, we still live in a world where local catastrophe reins, but people do not want to believe it can happen to them.

Indeed, the weather agency did issue a "red alert" about the storm.

Aemet first issued a “red alert” about the high probability of intense rain in the Valencia region at 7.36am

People said it lacked "urgency". There is no higher alert to be issued by the service. The criticism has been that it was not specific enough about the danger.

I have a suspicion that we would have seen a similar response had the state intervened and the storm not been "that bad."

We have not dealt with the changes in the political dynamics around issues in the face of climate change.

The NFU issue is about tax, but the truth in the lie is a complaint that farmers have no extra money after dealing with increasingly unstable and unpredictable growing seasons. The climate crisis here is expressing itself in a general anti-tax sentiment.

In Spain, predicting and responding to local climate-related storms has caused national anger towards the sitting government.

The response from the political classes is to talk about the need for "resiliency." But apart from evacuating the city, there is not much that people can do to avoid a storm that lasts for a few hours and dumps a year's worth of rain.

I am concerned about a different kind of resiliency. The resiliency of our political system.

No matter who is in power, they are going to get the blame for weather-related crises that are mostly out of their local control, in a similar vein to how all incumbent governments are getting blamed for high deficits and inflation after the entire world responded in the same way to the pandemic.

If we fail to link policies directly to the climate crisis, then political parties will devolve into channelling public anger in the usual directions.

The left must answer the question of how we can raise awareness about the climate crisis so as to connect policies, spending, taxation, production, and political orientations to the various local crises that are inevitable across the globe.

This is not a call for climate angst on the left. The calls demanding an end to everything that causes climate change are already being blunted by more immediate economic issues.

The left's materialist origins are mostly about complexity. The call for consciousness raising is a call to reveal how things really work, not just how they appear today through some uncritical lens.

Our analysis is about intersectionality, dialectics, emergent properties, complexity, and connectedness.

We must lean on these foundations if we are going to advance public solutions to economic problems within the context of all the crises of capitalism.

The Liberals announce cap and trade

Yesterday, while Unifor was calling for the regulation of downstream methane and VOCs (volatile organic compounds) in our oil and gas system, the Liberals announced their market mechanism to deal with upstream emissions.

The differences here are massive, but they sound like similar policies. Methane, emissions, climate change: It is largely the oil & gas industry that is to blame for these issues. But if you look a little closer, you can see these are on the exact opposite sides of the policy debate and opposite sides of the infrastructure.

What the Liberal government announced yesterday was a cap on emissions from the production of oil and gas. The mechanism that the Liberals are using to supposedly do this is a quasi-private market-mediated Cap-and-Trade system that relies on carbon pricing.

The issues:

- the focus is on carbon intensity of production and not total net emissions

- the regulatory cap was essentially written by the industry

- the investments are being made by the same companies that are paying the carbon price (some would say that this is the point)

- almost all the investments would have been made anyway

In response, the Liberals and liberal environmental organizations shout "Innovation!"

Yes, it is true that when profits are subsidized at certain phases of the investment cycle, innovations (i.e., new technology) are implemented. It is usually new firms that implement new technology first, so you would expect that a program subsidizing startup companies would lead to a net increase in new technology in the sector.

There really isn't any debate about that, but that's not really the point of a climate policy, is it?

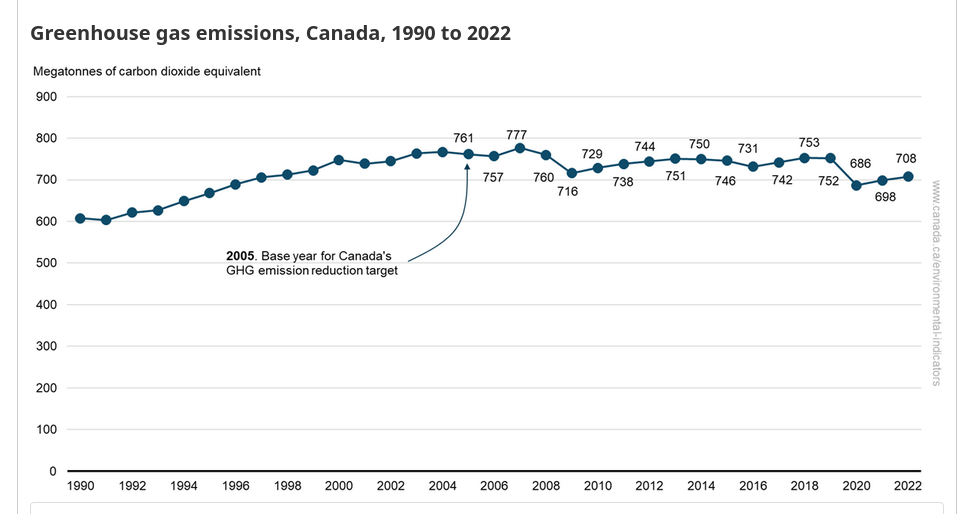

The goal is supposed to be reducing emissions.

The Unifor policy was a call for the direct regulation of company infrastructure in a way that reduces emissions. That is, energy companies are forced to re-invest their net revenue into the areas that actually have an effect on climate change.

The difference is that the Unifor ask would force regulated companies to hire a few hundred workers across Canada to fix leaks and upgrade infrastructure, thereby reducing our total emissions by 1% to 2%.

The Liberal plan is to claim victory over any dollar spent on "clean energy" and reduce the "intensity" of emissions. All while allowing the actual impact on the climate to be negligible.

Now, companies should be forced to invest in the type of energy production that is least bad for the environment. But they hardly need help doing this. Canada has some of the least efficiently produced oil and gas in the world. Fracking, in-situ mining, flaring, venting, burning fossil fuels to heat bitumen… the list goes on and on.

However, the main thing pushing Canada's energy companies to reduce emissions is that the demand for high-emitting fuel production (and their products) is under pressure. Regulations around total emissions put on products in Europe and the USA mean that Canada's production is priced out first. (We have discussed this previously.)

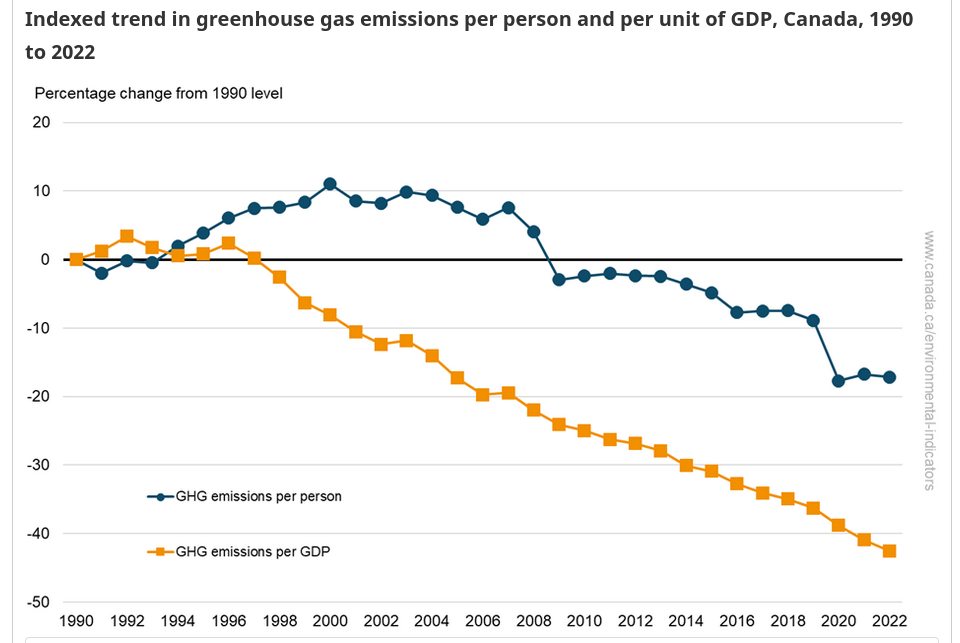

Companies already know this and their investments have been reducing the energy intensity through capital (instead of labour) investment:

The impact of $58B of investment has been limited in addressing the main issue: net emissions.

All the changes have to happen at the same time. Emissions intensity is important to stop the emissions from growing.

There are better ways to reduce emissions that we are forgetting, which are less sexy than celebrating "innovation", "startup", AI, and tech. Those less sexy, but actually effective, answers simply involve workers fixing the leaks and making products that shift the demand and use of fossil fuels.

Decoupling

The word that the government is using is "decoupling".

Decoupling is said to be essential to sustain economic growth but decouples this growth from rises in emissions. Of course, economic growth in areas that are not fossil-fuel dependent are already decoupled from emissions.

The narrative is very similar to "emissions intensity", and the government will continue to face criticism from environmental groups for not actually acting to reduce emissions.

From the labour perspective, decoupling is only a positive thing if it is investment in the expansion of real alternatives at industrial scale.

There is little reason to be excited by economic growth generated by startup capital speculating on niche chemical production or changes to things like cement production using technology based in the USA.

There is little gained from taxing oil and gas companies, then giving that money right back to them for investing in things that they were going to invest in anyway. This includes reducing the emissions intensity of their refining processes.

This does not mean that I think we should be critical of the government announcements. They are announcements from a government that wants to take credit for private sector initiatives that are even tangentially related to their programs.

And we like the focus on the (ever so slight) tether between union jobs and government money/program support.

But without proper regulation of the industry that forces (not just begs for) investment in leak mitigation and in the demand side of our economy, then we are stuck.