November 27, 2023

Food, trade, and climate change

Food supply chains are an important part of the battle for climate sustainability.

The previous 40 years has seen a lengthening of the supply chains of food. With this lengthening, the average amount of fuel being burned has, on average, gone up.

Climate scientists have been attempting to measure the impact of distance on emissions. This is, surprisingly, a very new question to ask and getting data has been very difficult.

- Transporting food: 19% of all food emissions (on average)

- Just 12.5% of people (in high income countries) account for 46% of these emissions

- Food: 30% of total emissions.

- Food transport alone: 6% of total emissions.

- Vegetable and fruit consumption: 36% of food emissions, twice the amount of greenhouse gases released during their production.

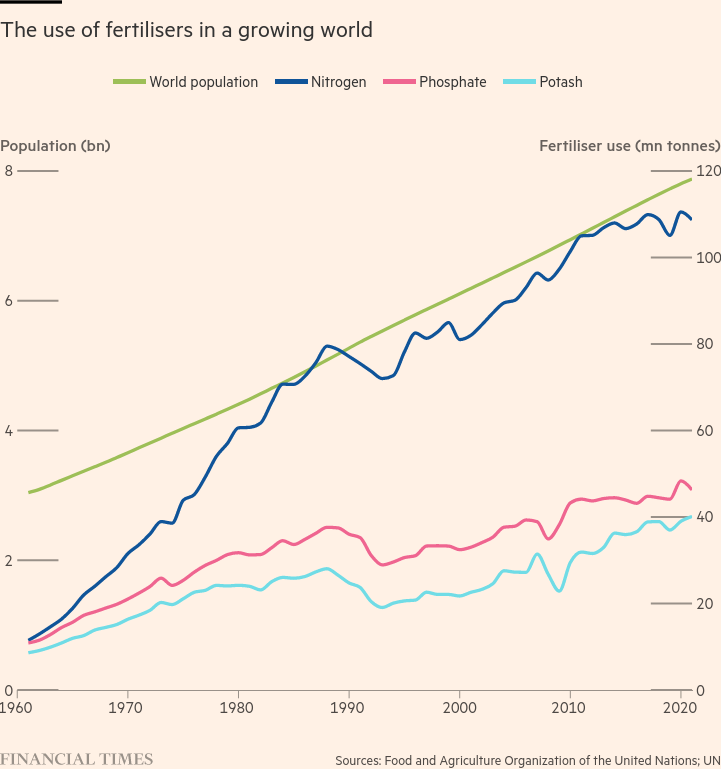

The other section of food production not talked about in polite company is mining the inputs to fertilizer.

Canada produces potash for the local and global food market as it contains potassium and because it is more abundant in Saskatchewan than most anywhere else in the world.

These are essentially salt deposits and store oil, natural gas, salts, and other critical minerals—all competing for investment.

For food, fertilizers are exported and food stuffs (and non-edible plants like flowers) are imported. It is a massive movement of minerals in one form and then another. And no one is really counting the impacts.

We talk about greening the planet, but we still do not have a handle on our supply chains enough to even measure emissions of this process. Never mind that we must understand these processes to shift our supply chains and production habits to limit emissions.

It is a reminder that while we talk about "supply chain resilience" and greening those supply chains, we have let forty years of deregulation and free trade expansion in search of reduced costs drive investment decisions as we massively expand our food supply.

The search for efficiency in production is about growing more for less. Undoing some of the worst aspects of this production will have real and lasting impacts on the cost of food production.

Some companies are shifting supply to reduce what they call "food miles" in an attempt to green(wash) their businesses. The impact of this is not only positive. Undoing forty years of supply chain development has very real impacts on the economies of mostly poorer countries and farmers who were pushed to invest in development of these industries. Many Sub-Saharan African countries and communities are being hit hard by some of these changes.

The impact is so large that an entire part of the COP meetings on climate change are dedicated to the distribution of aid and other failed mechanisms of dealing with massive shifts in production.

The result so far is a lot of empty cargo planes flying around. They are full of imports heading one way and empty flying back as supply chains shift too quickly.

All of these impact the price of goods.

And, those costs feed into the price of food.

Food and the supply chains established around its transport is a clear example of why a market-based approach to climate mitigation will fail. Increasing prices for food cause revolutions to happen. However, without an answer to this "cost of inputs" question, it is hardly guaranteed that the outcome of any revolt will be progressive.