November 20, 2024

Inflation across countries; central bank rates

- UK inflation is higher than expected

- South Africa is lower than expected

- USA inflation is expected to be higher than desired (because of Trump and the IRA)

- European wage growth is "too high" and the central banks are concerned that will affect inflation.

- Euro Area inflation falls continue to stagnate.

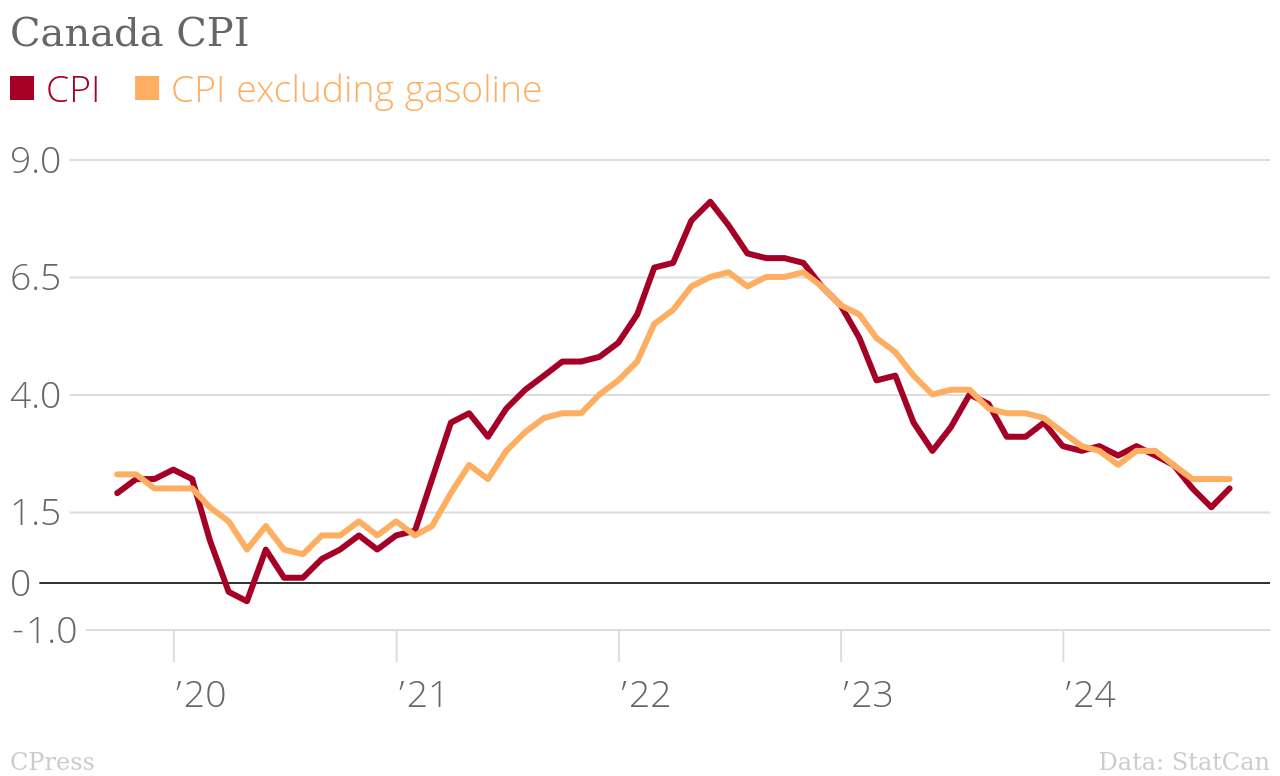

- Canada's inflation is not coming down as quickly as the central bank wants.

It sounds almost like we have returned to the 2021s in the debate of where inflation might go and the central banks policy program in response.

This time it is different, however. Inflation is not going in the same direction around the world and people have started to question central bank control over that inflation through interest rate adjustments. This questioning is because interest rate adjustments are seen as holding back economic growth and hurting high-debt carries government and consumers.

This is because, as we have discussed many times, neoclassical theory does not really have a "theory of inflation". The field kind of agrees that monetary policy should adjust if it goes up and down, but when it comes to exactly why inflation changes they have not a clue.

Let's start in the EU to hammer home our point.

The European Central Bank is very neoclassical. It still believes that wage-price spirals are a thing and thinks inflation is that there is too much money floating around because of too high wages.

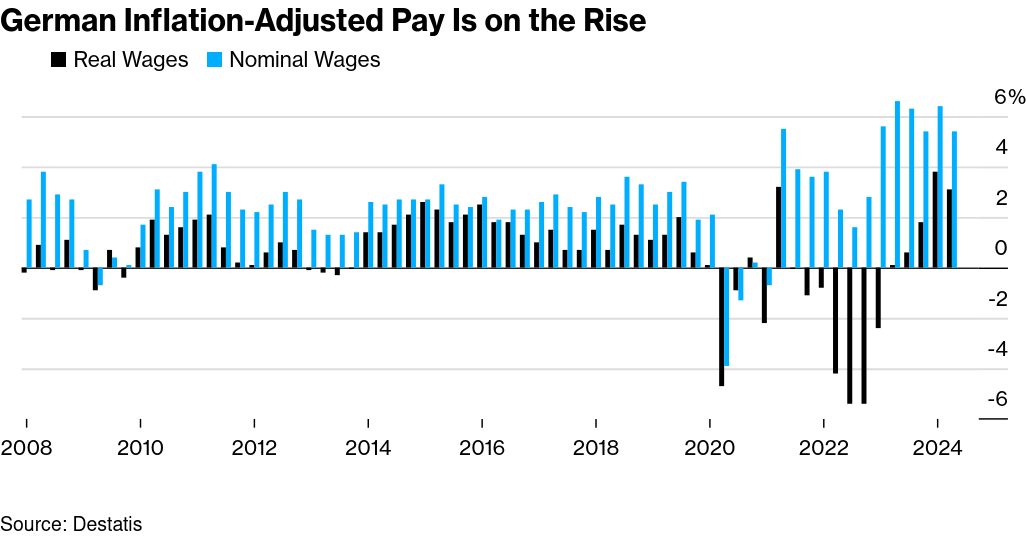

The ECB folks see a graph like the one below and they freak out that interest rates are way too low. Back a couple years ago and you would have seen interest rates go up. But, not this year. What has changed?

They are competing with the USA and other countries that are using lower interest rates to prop-up their back-sliding economies (wars, shifting trade programs, and international competition in the energy transition).

Industrial production jobs that are actually around (or will be around after plant closures) are still paying OK because of union contracts. But, that also means that wage growth has been locked in.

Take Germany, specifically:

Even if non-union sectors of the economy are rising fast, IG Metall contracts covering 3.9M workers will be sustained.

- 2% in April 2025

- 3.1% in 2026

This is far below the market-mediate wage growth in the lower paid sectors of the economy.

The direction of inflation and the politics of that matters more here than the actual data because they do not really know what is controlling inflation. It is like the Neanderthal and tides. They know they go up and down and have to move their fishing spots, but they do not know why they move.

The European central bankers have decided, even though the circumstances are basically the same as they were when interest rates went up, that interest rates should continue to come down.

This is not unexpected and likely consistent with their mission to balance growth with inflation, it just does not point to a coherent data-based independent program.

In the USA, things are a bit different. The government is now discussing whether or not the central bank should be independent. (For this discussion to work, you have to suspend disbelief and assume that the Federal Reserve was independent to start with.)

What will happen to interest rates as they relate to inflation over the next four years? We have no idea.

The Federal Reserve thinks of itself as independent(ish) from government; responding to economic indicators set by government in near-mechanical ways. But, the way that it responds is not exactly apolitical. Rising interest rates to force workers to pay for inflation is not the only way that even neoclassical economists know of responding to inflation.

This debate, apparently goes back to 1935 in the USA according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Mostly because this was the rise of fascist ideology which wanted to be able to control all aspects of the economy.

The Senate back then decided that their central banks should be more independent than not since government officials all agreed on the ideological framework capital wanted to work under.

Even though many different renditions of economic ideology came and went from 1935 to today, that narrative of the "independence" of the central bank was sustained and expanded to the myth of "apolitical" and technocratic decision making.

Why is this conversation important?

If the USA decides, under Trump, that central banks should operate more under the whim of the president then it is unlikely that all the other central banks in capitalist countries will be able to sustain their narrative around independence.

The impact is going to be a different kind of decision making for the macro aspects of the economy in the central banks.

You may think that this could be good new for workers. After all, the bankers acting independently hardly had workers' interests in mind. However, that is not the likely outcome.

What the Trump administration is wanting is the ability to drive economic growth similar to pre-2009 levels. This means using the government's bank to provide profit subsidies to business.

There is always a cost of pumping-up the economy, and giving capital more money than they create in value will have impacts on inflation.

How would that be different from today?

The kind of profit subsidy to endemic capital is what we saw in the 2009 to 2019 decade. This is likely what gave us super high inflation.

A continued neoclassical view of wage growth and inflation means that wage pressure will be a focus.

Link this to the loud pronouncements from the Post Keynesians (adopted by neoclassicals recently) centre left that price controls (and thus wage controls) are an option and you have a return to that 1935 conversation about fascist economics.

We may be seeing the start of the policy frame that will be used to rescue USA capital from its current malaise.

Back to the different inflation directions.

The fact that inflation is going in different directions (or hovering higher than pre-2019) around the world means that these policies will drive different conversations in different countries.

If central banks abandon their 90 year groundings of "independence" then it might not be inflation that we are looking at to guide central bank policy. It might be currency wars, tariffs, and competition between endemic growth that drive the discussion of what central banks do.

That might mean a very different policy world than the one we all grew up in.