November 17, 2022

Electric vehicles and economic growth

Ford Motor Company has stated that it takes 40% fewer workers to make electric cars compared to gas cars. This is partly because electric car parts are built elsewhere such as batteries, electronics, electric motors. It is also because electric engines are significantly simpler in design.

Making electric vehicles will require 40 per cent fewer workers than building cars and trucks powered by petrol, the chief executive of Ford has declared, saying the carmaker needs to produce more parts in-house so that “everyone has a role” in the transition.

Jim Farley warned on Tuesday of “storm clouds” in the next phase of switching to EVs. His company has set a goal of half of global sales coming from EVs by 2030, part of a broader shift among manufacturers.

In Germany, a report expressed concern that they will lose 400,000 workers in the sector if they do not bring all of the currently outsourced production back into the country.

Car "manufacturing" in the USA is mostly a process of putting the parts together with some parts suppliers building the mass of bits that make up things like breaks, seating, lights, mirrors, internals, and powertrain. These parts suppliers source their materials and electronics from technically expensive supply chains (so expensive it ends up being monopolistic).

The issue with the chip shortage starting in 2021 was to do with this complex supply chain system. The solution is to make these monopolistic parts "in house". The issue with in house is these are very complex systems built elsewhere and it takes a long time (and a lot of money/debt) to build in house knowledge and skill capacity.

An issue faced by the public sector when it outsources services and/or production.

In addition, building new supply chains from scratch inside a country (or group of countries as with the Auto Pact) is going to take a long time. Ownership of mines, logistics, skill building, firms that design, build, test and print chips, along with the processing of the materials necessary for this production process currently do not exist here at any scale.

What is missing from this ambitious aspiration is the cost of debt and the cost of labour—which is what drove the outsourcing in the first place. Capital will come to the government to subsidize this process and that will take the form of wage suppression and/or debt/tax subsidies.

The only way to avoid the massive profit subsidy from bankrupting public services will be to find the most economically efficient way to build local manufacturing. Something that the "market" is not set-up to do.

As with all production, employment in the auto sector does not exist in isolation. Unfortunately, so called "Just Transition" is still something that we have not gotten policy implemented for, never mind an industrial program that is coherent. Losing this many manufacturing jobs in one large employment sector is only something at scale that is happening worker by worker at the smaller firm level. Any policy response has to deal with all that movement.

Fall economic statements

This new tradition of releasing statements about the economy between budget (which are just budgets) has given right-wing governments even more opportunities to make cuts or announce profit subsidies.

Jeremy Hunt, chancellor, confronted the fiscal “storm” battering Britain on Thursday, announcing £55bn of tax rises and spending cuts intended to restore the country’s reputation and shore up its frail balance sheet.

Two months after Kwasi Kwarteng, his predecessor, sparked market panic with a “mini” Budget that included £45bn of unfunded tax cuts, Hunt’s Autumn Statement turned Tory economic policy on its head.

With Britain’s economy sliding into recession, the official forecasts highlighted the challenge for household and public finances, both of which will be strained by predicted 2023 inflation of 7.4 per cent. The economy is projected to contract by 1.4 per cent and is not forecast to recover to pre-pandemic levels until the end of 2024.

The pound was 0.8 per cent lower on the day at $1.181 against the dollar … (FT)

The recent economic statements in Canada are not as drastic, but are still filled with the wrong medicine for the times. Rapidly shifting economic conditions and bad models designed for a different era make for hard predictions.

Almost all predictions in the Ontario budget have been shown to be incorrect. Now, we could ascribe malice to the predictions, but even the malice version is based on accepted models.

We are in uncharted territory. The problem is the compass is also broken.

Central Bankers do not care what you think

The International Monetary Fund’s First Deputy Managing Director, Gita Gopinath, said a key question for 2023 is how long central banks will keep interest rates elevated as they work to tame the highest inflation in four decades. Photographer: Bryan van der Beek/Bloomberg

She said the fund expects the Federal Reserve and its peers in other major economies to keep rates at 4% or above for the duration of the year, because the risk of pivoting too soon is allowing inflation to become entrenched.

“It is very important for central banks to stay the course,” Gopinath said. “We’ve had false dawns before,” she cautioned, referring to recent data indicating that inflation had peaked in some countries.

The discussions at the G20 and the New Economy Forum have focused on metrics that have never worked. So, the safest bet for these managers of the capitalist economy is to drive things into the dirt.

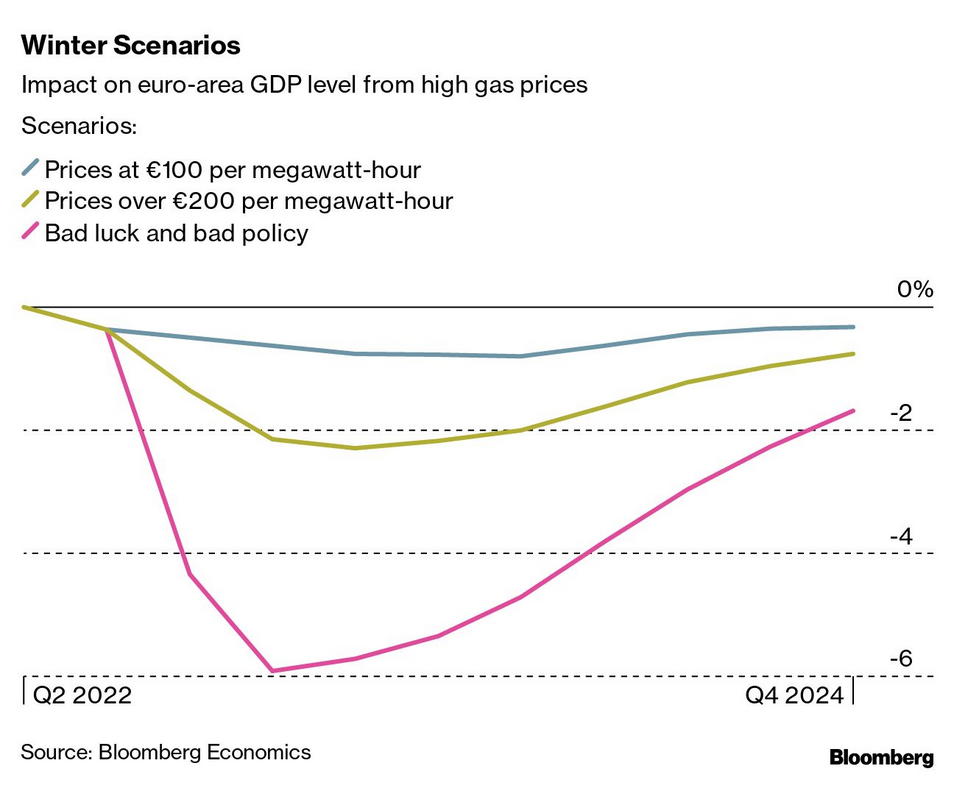

They should be more worried about the Euro collapse in growth due to the war in Ukraine: