March 15, 2022

Russia Default

The outcome is complex as there are competing interests in the fallout of a default. Russia is threatening to – essentially – not pay its debts or pay them in currency that cannot make it to investors outside the country.

It is important to remember that the last time a foreign-currency debt default came was in 1918, when the Bolsheviks rejected Tsarist-era debts following the Russian Revolution.

But a “normal” restructuring seems unlikely in Russia’s case. The sanctions are designed to lock the country out of global bond markets and the participation of western investors in any new debt sales is forbidden.

Instead, investors will probably have to sit tight, writing off their Russian bonds and awaiting a de-escalation in the Ukraine conflict that might lead to an easing of sanctions. Some may actually want to quickly vote to demand immediate repayment and get court judgments from US and UK judges that allow them to try to seize overseas Russian assets, to ratchet up pressure on Moscow.

In the meantime, some investors will be hoping that the failure to make interest payments triggers a payout on credit-default swaps — insurance-like derivatives used to protect against default. The decision will be made by a finance industry “determinations committee”, made up of representatives of big banks and asset managers active in the CDS market. The swaps may not end up helping bondholders, however, because the financial sanctions could snarl up the intricate system used to settle the contracts.

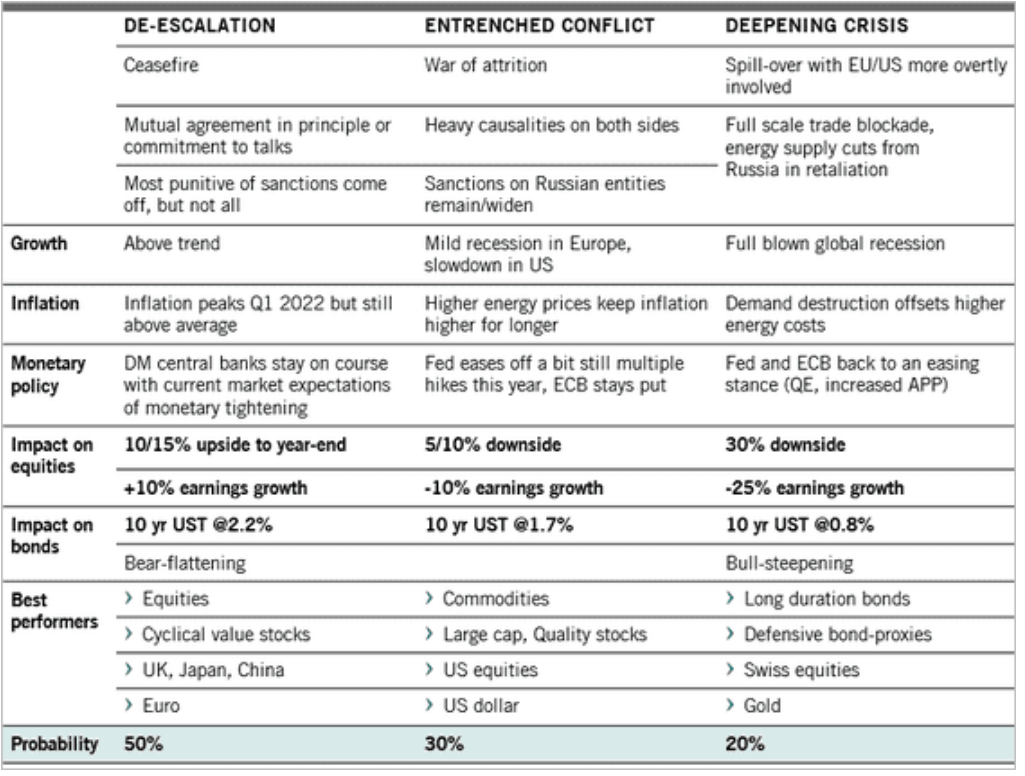

Economic modeling of the impact of the war

WHO will look to create open source mRNA vaccines

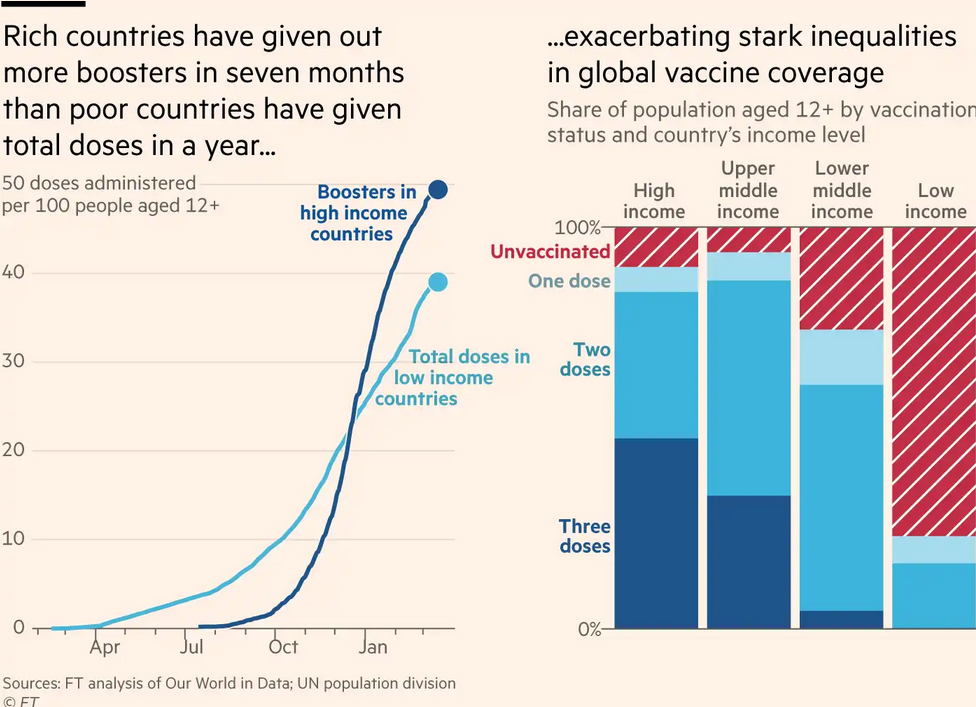

They kind of have to since the US is engaging in international biowarfare by artificially restricting access to mRNA vaccine production and blocking cheaper alternatives such as the ones developed in Cuba.

Spearheaded by the WHO, the setting for this radical overhaul is a series of nondescript warehouses on a Cape Town industrial estate, next to a factory-sale bed shop. It is there, at the headquarters of Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines, a South African start-up, that late one night in January a scientist walked into the office of Petro Terblanche, the company’s managing director, and announced a breakthrough. Afrigen, a member of a hub — of scientists and pharmaceutical companies — created to develop mRNA vaccines, had successfully formulated a replica of Moderna’s Covid vaccine.

The Cape Town initiative is part of a new push by global health authorities, academics and philanthropists to address that and promote alternatives to “Big Pharma’s” business model, which relies on legally enforceable patent protections to raise investment to fund new drugs. The chronic lack of access to vaccines in the developing world has emboldened some researchers to embrace the concept of “open-source pharma” — an idea modelled on the free software movement, which encourages collaboration and sharing to improve code.

Even if it passes all of its regulatory hurdles, Afrigen’s will not be the first open-source vaccine to go into people’s arms, although it would be the first mRNA one to do so. Some countries, such as Cuba, have invested heavily over the years to create a public and domestic biotech sector to help produce drugs if and when needed.

It now has one of the world’s highest Covid vaccination rates in adults and children above the age of two and has been using protein-based shots, a more traditional type of technology that is easier to make and store.

“[Cuba’s] public patents are free to facilitate tech transfer,” says Fabrizio Chiodo, a scientific researcher at Italy’s national research centre and Cuba’s Finlay institute, “with a royalty to be paid [to the state] on a case-by-case basis”.

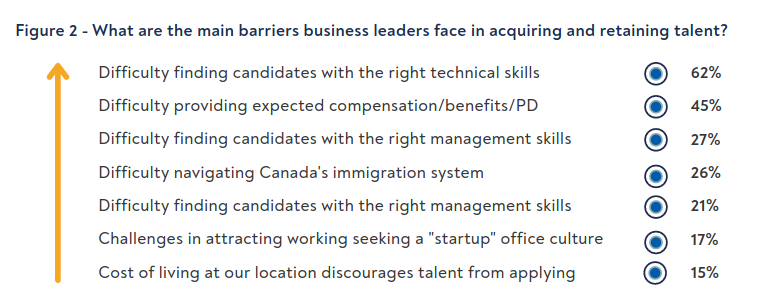

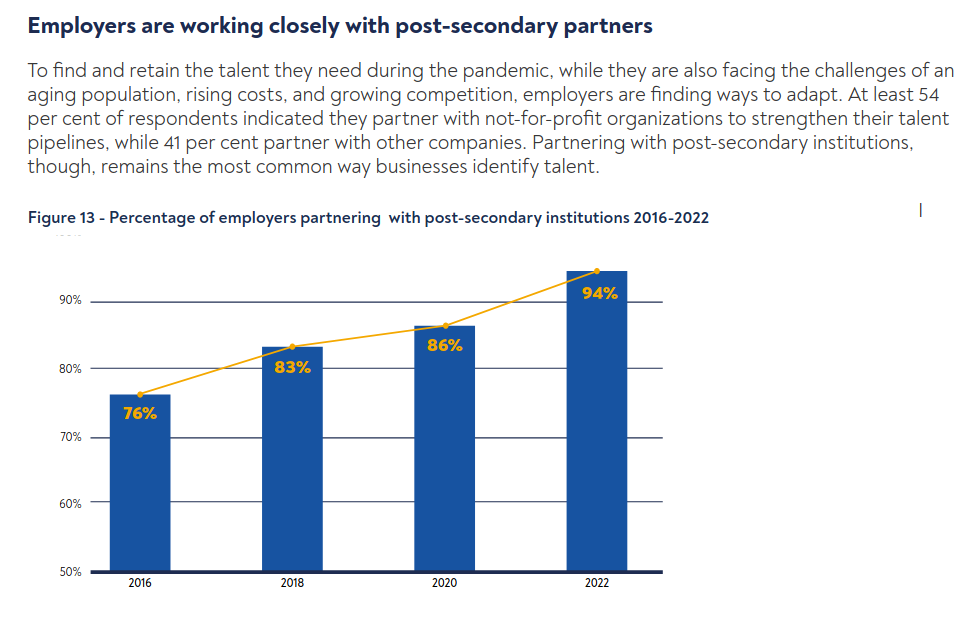

Business want full government "support" for soft skills

The focus of capital in Canada is to increase the supply of workers with interchangeable skills. This is not new, of course, but it is becoming the main focus of their lobbying efforts around post-secondary education.

Microcredits are being demanded at this policy level – even though there is absolutely no evidence this will have a positive impact on worker availability.

As you can see here, the issues are related to not wanting to pay workers more for their higher skills.

And, that employers are looking to the PSE system to directly provide them with workers specifically trained for their short-term needs. The government's policy is directly aligned with this employer desire.

The problem, again, is that there is no indication that this is a good idea. And, it fully undermines the education system.

Covid booster hesitancy in Canada

All the things you would think about those who are not getting boostered apply: less likely to follow public health guidance, less likely to have higher education, more likely to not have access to correct information.

Working class organizations are not doing a good job of outreach to these folks.

Results from the survey show that in the fall of 2021, 86% of Canadians aged 12 and older reported that they were very or somewhat likely to get a COVID-19 booster dose. Reported intentions may not always translate into actual booster dose uptake across Canada, where according to the Public Health Agency of Canada, as of March 6, 2022, 56% of Canadians aged 18 and older were fully vaccinated and had a booster dose.