July 26, 2023

Productivity

It is a word that managers (are supposed to) fret over almost 100% of their time. Increasing productivity might be a goal, but advanced capitalist countries' capacity use and poor economic analysis harm the ability to make headway.

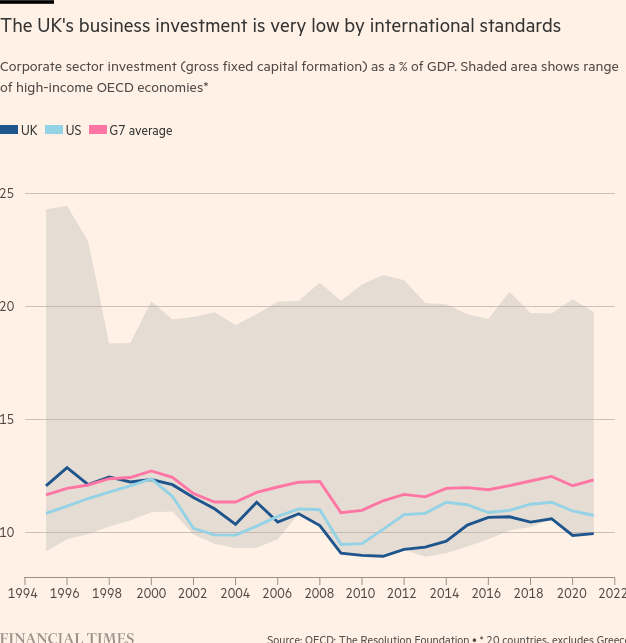

Most advanced capitalist countries (advanced in "age", not wisdom), are lagging in their productivity growth since 2009.

Most MBA graduates think that "productivity" is about getting more out of "workers" by trying to get them to work smarter, faster, or more efficiently. They are not strictly wrong here, productivity is about doing those things, but the focus is all wrong. You can improve productivity by speeding up the line, but that is not how general productivity increases.

Productivity is a product of investment in new technology and replacing workers with machines. There are, as one might guess, many different barriers under capitalism to increasing productivity—beyond the fact that sometimes the machine you want does not exist yet.

Capital is about making profits. Maximizing profits is the goal, of course. But, when it comes to calculations about investments in automation and replacing workers with machines, it is a difficult and risky proposition. In many cases in advanced manufacturing, the answer is affected by this risk. While investment and implementation of new technology may increase productivity and boost profits, the long-term costs of those technologies such as fixed investments not being used fully, debt repayment costs, and repair time can drag the profits back down.

If you are a well established, highly mechanized company competing with other very large companies, investment in new upgrades may not be worth it.

This is the place that the UK, Canada, and the USA are in. Unfortunately, productivity is the main driver of profit growth since capital has been beating labour for the spoils of productivity growth for a long time.

What does this mean? It means that we have not seen the end of fad-driven management practices and intense pressure on workers to speed-up their lines. But, it also means that there is an intense pressure to implement "AI" in attempts to replace workers—even if quality is reduced.

AI's promises here (or rather the promises of companies selling AI) cannot be overstated. People laugh at language models being "not great", but they do not have to be great to affect jobs. They just have to be good enough to be implemented in the work environment.

The best defense of the working class against this shift two pronged. We need higher wages along with regulation limiting the misapplication of the technology. If we get one without the other, there will be job losses in advanced capitalist countries.

Why do we have to keep reminding people this? Because many on the left are confused about the implementation of technology in the workplace. Either they oppose it or they do not think it is such a big deal as "there are jobs created elsewhere in the economy". This is true, but this is hardly a salve for the worker who has been replaced. Especially when we do nothing for that worker other than suggest they get "retrained".

Oil

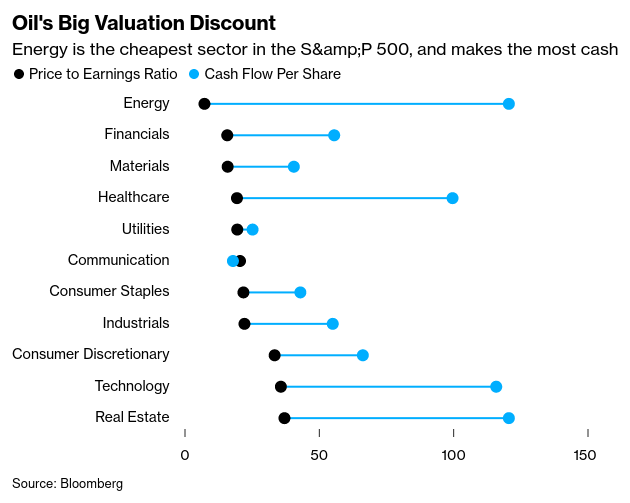

Offshore drilling is going to make a revival soon. Especially with all the cash that is piling-up at oil companies.

There is no better place to invest right now—if only care about shareholder profits.

For all the talk of the inability to withstand carbon pricing, divestment campaigns, and ESG-driven investment programs, oil and gas capital is just fine. Warren Buffet is one of the largest investors in oil and gas and he constantly thanks divestment and ESG campaigns for keeping the price of oil investments low and, subsequently, their ratio to cash returns very high.

Oil demand continues to be sky high.

Global oil demand is projected to climb by 2.2 mb/d in 2023 to reach 102.1 mb/d, a new record. However, persistent macroeconomic headwinds, apparent in a deepening manufacturing slump, have led us to revise our 2023 growth estimate lower for the first time this year, by 220 kb/d. Buoyed by surging petrochemical use, China will account for 70% of global gains, while OECD consumption remains anaemic. Growth will slow to 1.1 mb/d in 2024. (OMR-IEA)

The only place that we are seeing oil demand coming under pressure is from higher interest rates' broader effect on production. Which tells you something about the nature of our policy on carbon emissions.