July 20, 2022

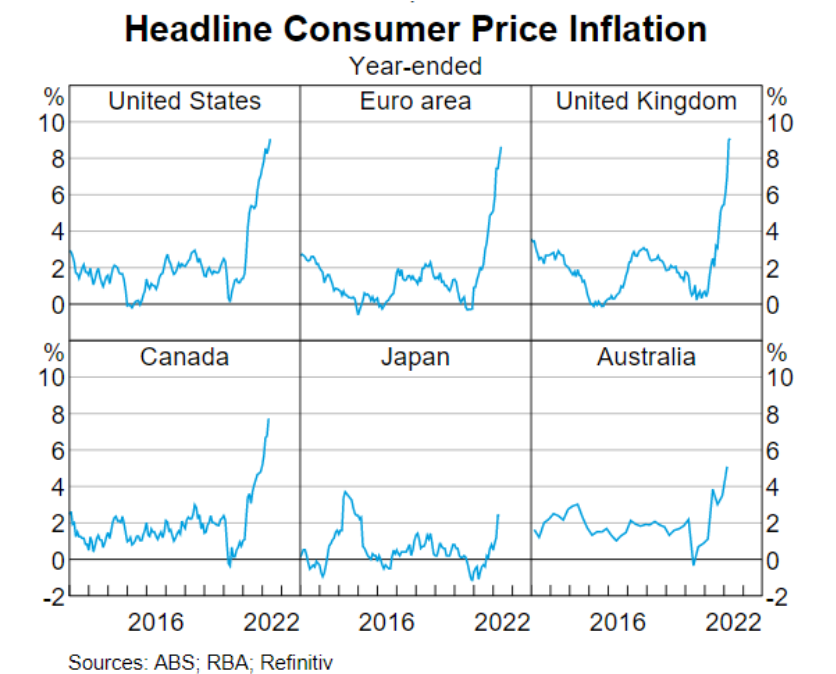

CPI

Consumer Price Indexes are all the rage in reporting "inflation". But, what do these graphs really mean?

Here is a pull quote from the FT this morning:

Economic data Canada’s consumer price index is expected to rise to 8.4 per cent during June after hitting 7.7 per cent the previous month, the quickest pace in almost four decades. In the US, existing home sales are expected to have dropped for the fifth straight month to a rate of 5.38mn in June from 5.41mn the previous month, against a backdrop of rising mortgage rates and record prices weakening demand from potential buyers. (FT)

CPI released this morning:

and CPI excluding gasoline.png)

CPI measures compared:

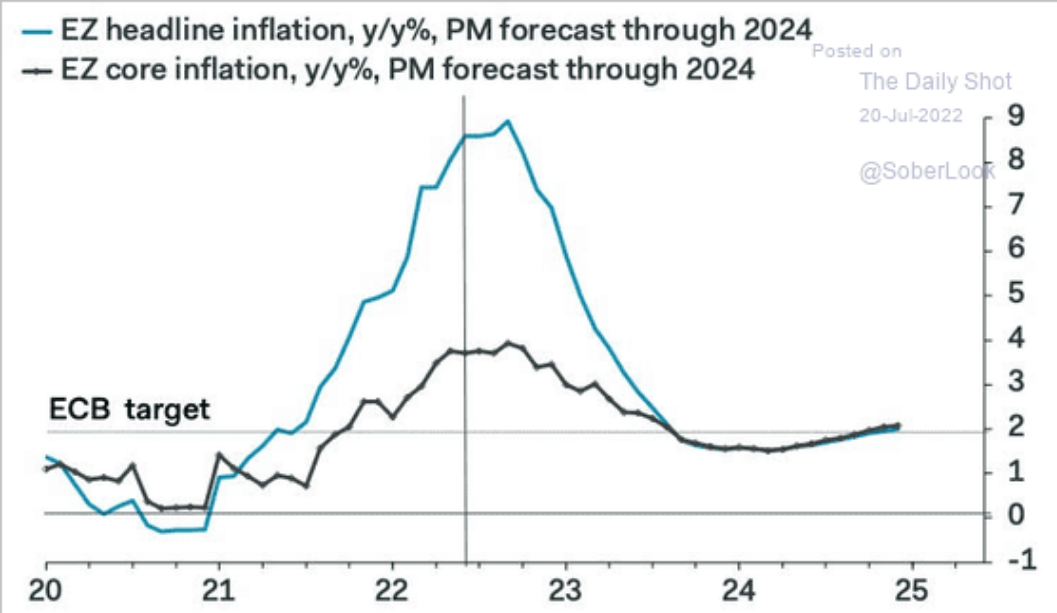

And, a nice graph outlining European prices showing they are expected to continue to rise:

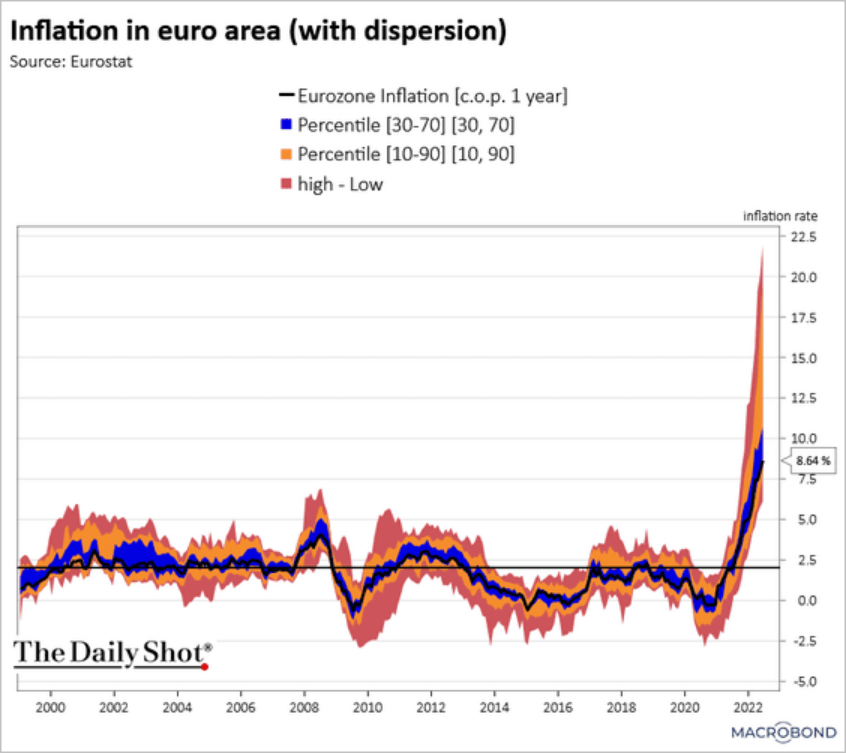

However, CPI measures are not the whole story even when we are talking about CPI.

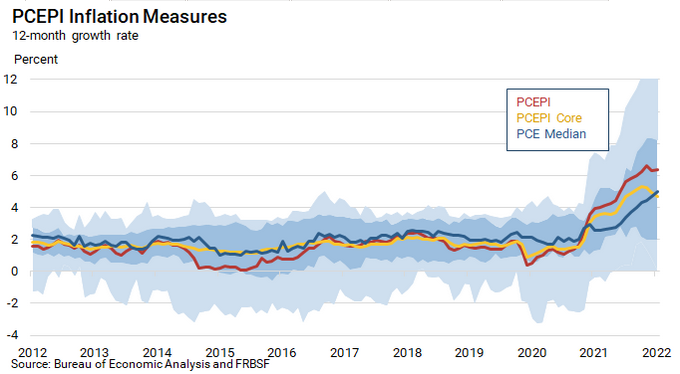

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco has some interesting data on personal consumption expenditure price index (PCEPI) dispersion. Dispersion shows the range of changes in prices of the goods in the basket as it relates to consumers purchasing those goods at that price.

Looking at CPI is fine for headlines, but there are so many ways to represent changes in prices of goods and consumer decisions to buy that good.

You change your purchasing habits as the prices of goods change—even when inflation is not high. And, just because the "price" of good changes do not mean consumers are purchasing that good at that price.

This should be obvious, but the dominant narrative does not talk about prices this way.

New Keynesian economics (the neoclassical form that drives central bank thinking) looks at dispersion as part of their theory of prices. Dispersion (the error around the price measure and its effect on the real general price level) is about including whether a thing at a certain price is actually sold.

If no one buys your widget, it does not really matter if your widget's price has risen (or, in the case of inflation, that you can no longer buy it with the money you could yesterday).

Why is this important? Because price dispersion is the neoclassical version of profit rate and competition. Price dispersions shows that there is not a standard rate of profit and that consumers do not just take prices as set by the seller. New Keynesians (neoclassical) see this as a deviation from the norm.

Classical (Marxists) point out that it is the expected scenario in a real economy.

Classical theory also looks to the actual economy in terms of addressing tightness in capacity utilization and profitability.

If there is no sense that profits are on the horizon, you do not get investment.

Well, the short-term profit rate expectation right now is very low:

There is still money in the system that should not be there, there is no increased production to create new value growth, capacity utilization is high, and profits are declining.

Sounds like a high inflation recession to me.

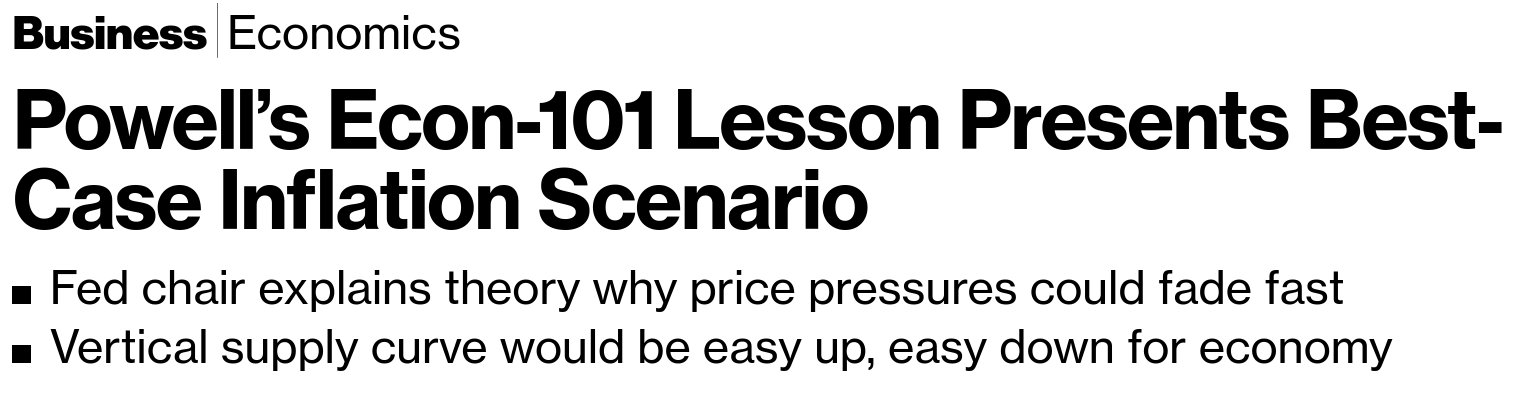

Unfortunately, central bankers do not see it that way:

Powell thinks that because prices are going up, more investment is on its way—because that is what his Econ 101 textbook from the 80s says will happen. For Powell, it is all about supply and demand.

Part of the problem with this idea is that it is stupid. Or, at least would be except USA central bank heads can increase interest rates so high that they drive the economy into a state where higher unemployment becomes a real thing. High unemployment will drive wages down and eventually (after the recession) profitability will be pushed back up with interest rates being pushed back down.

This is really stupid.

We do not have to destroy the economy (and working people's lives) to get investment in production. And, you do not need to cause unemployment to create a supply of labour into productive enterprise.

But, stupid is what these (mostly) guys are about.

The issue that is front and centre in the stupid New Keynesian (neoclassical) thinking is that labour supply works like supply of products. New Keynesians say we need more supply of unemployed labour, so they force people out of their cozy "unproductive" jobs (by closing unproductive businesses) so they have to work harder in "productive" jobs.

This isn't the economy we want, but it is the economy we are being pushed into.

Heat

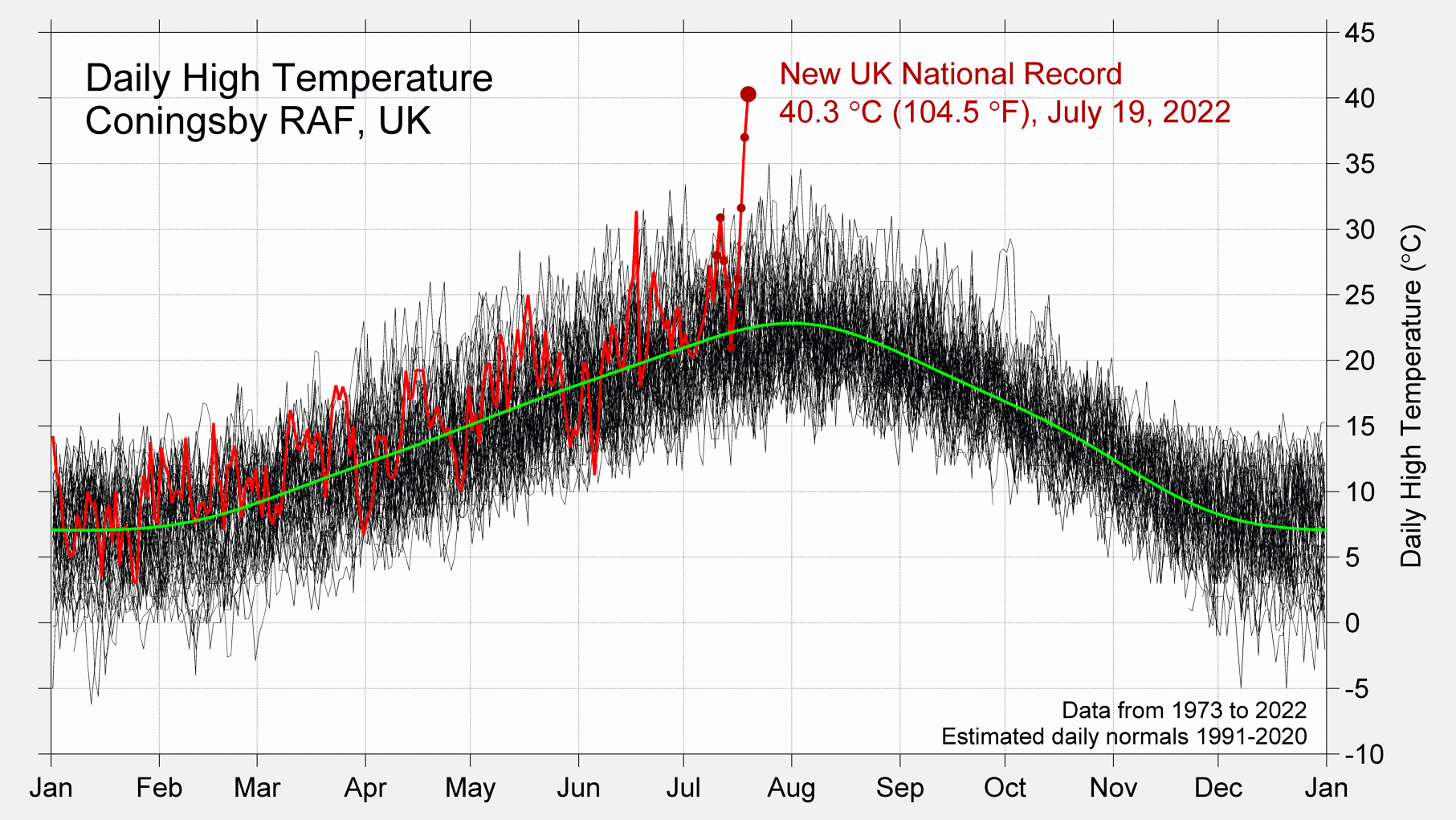

We continue to see graphs like this, but is it affecting attitudes, investment, and shifting production patterns that could impact the climate positively?

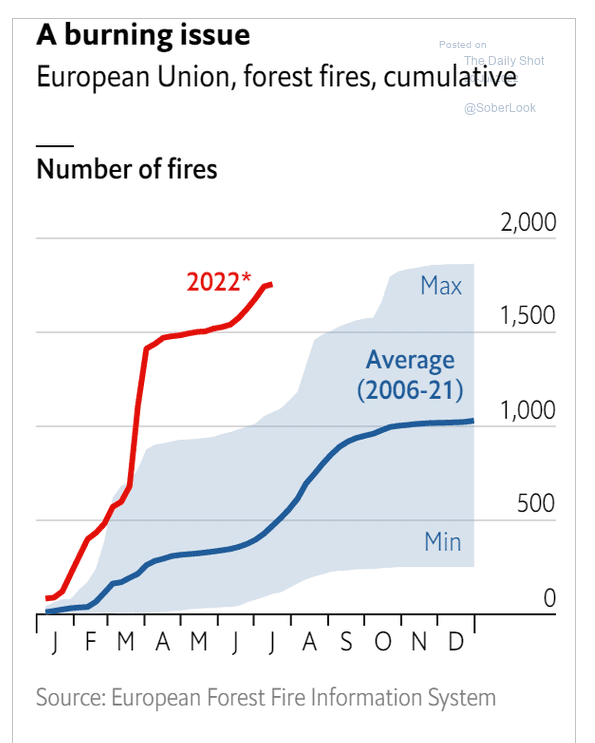

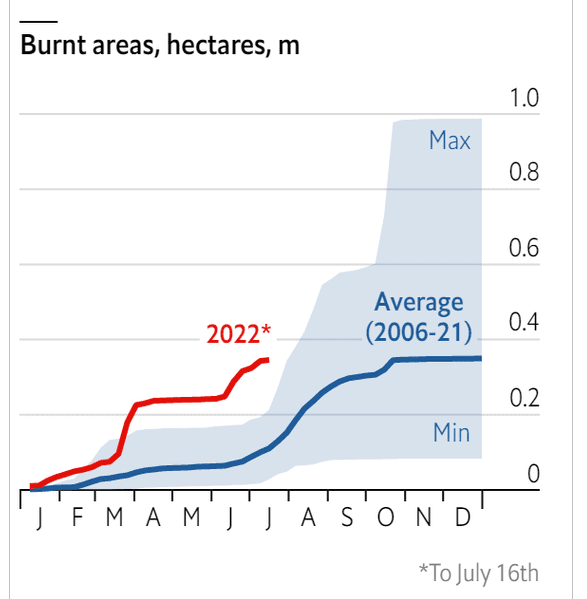

It isn't just the heat:

Of course, forest fires do not make the climate crisis easier to deal with.

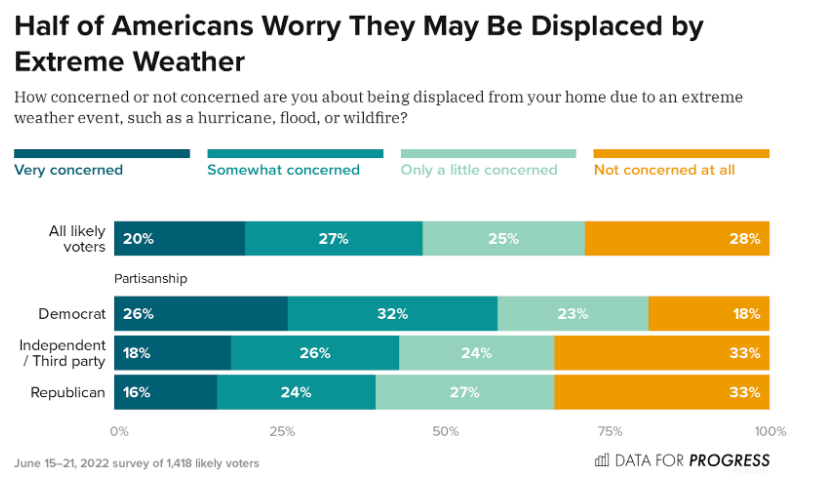

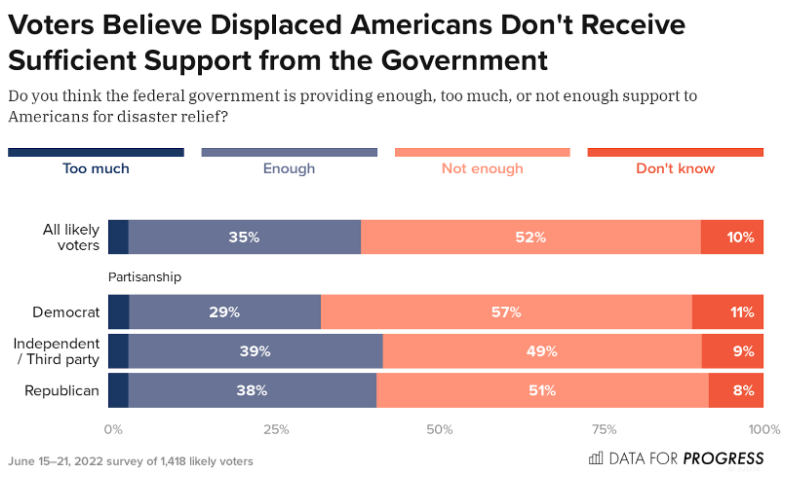

Speaking of, a plurality of people in the USA get that climate change is going to affect them and think the government is not doing enough to support people affected by extreme weather events.

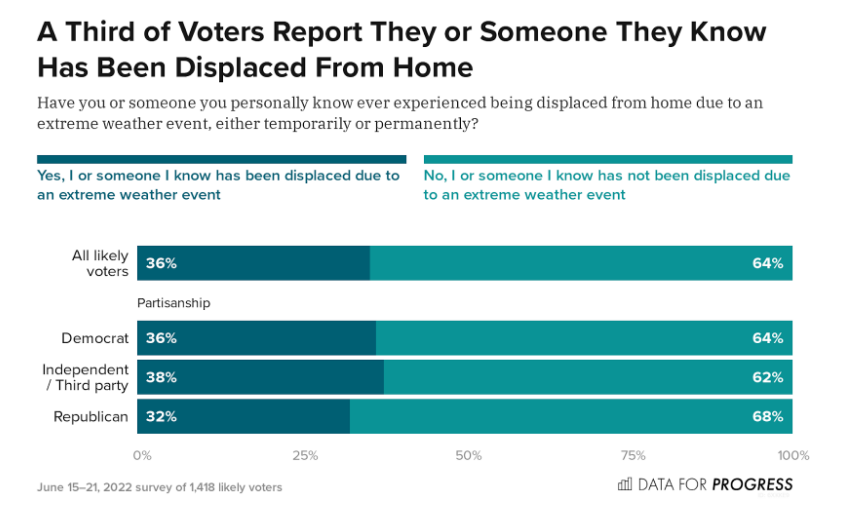

Seems to go along with 1/3 of people knowing someone who is directly affected by extreme weather.

Yet, the response seems completely absent.