January 9, 2024

Public debt

There is a growing chorus of conservative economists pointing at public debt and using the words worrisome, near-historically high, unmoored, divorced from the reality of the market, deluge of bond sales, and out of control.

What's the deal?

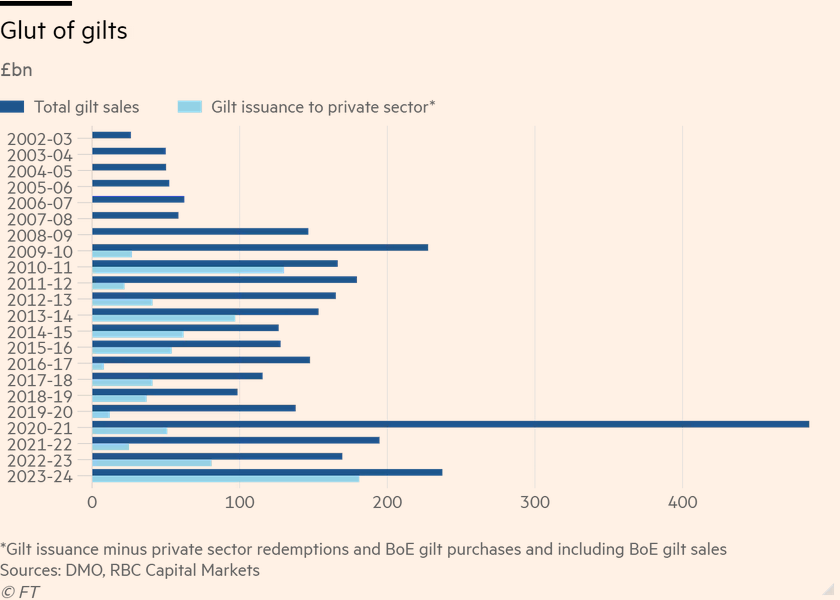

It seems as though public borrowing is set to be almost as high as it was during the massive increase of the pandemic spending.

- Emerging markets public debt: 68.2% of GDP in 2023

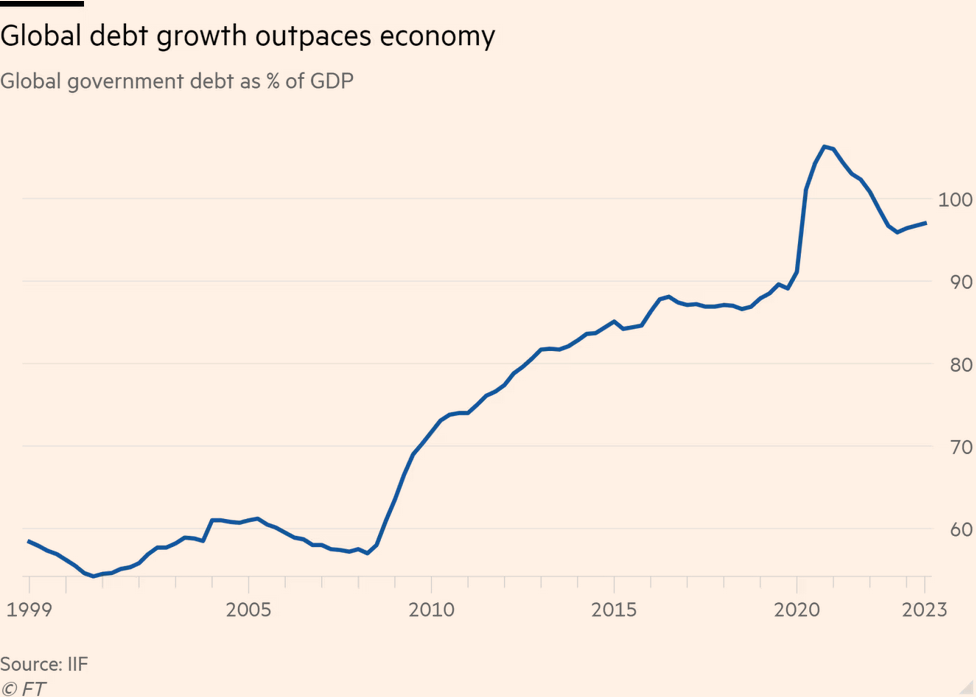

For the world as a whole:

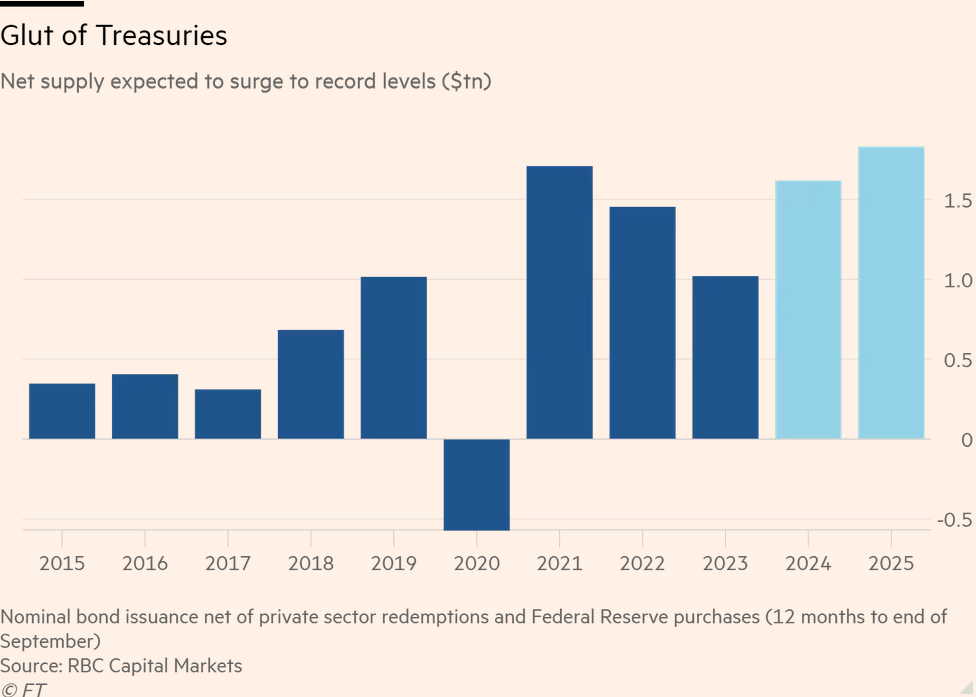

USA borrowing because of the large investments in profit subsidies and production supports:

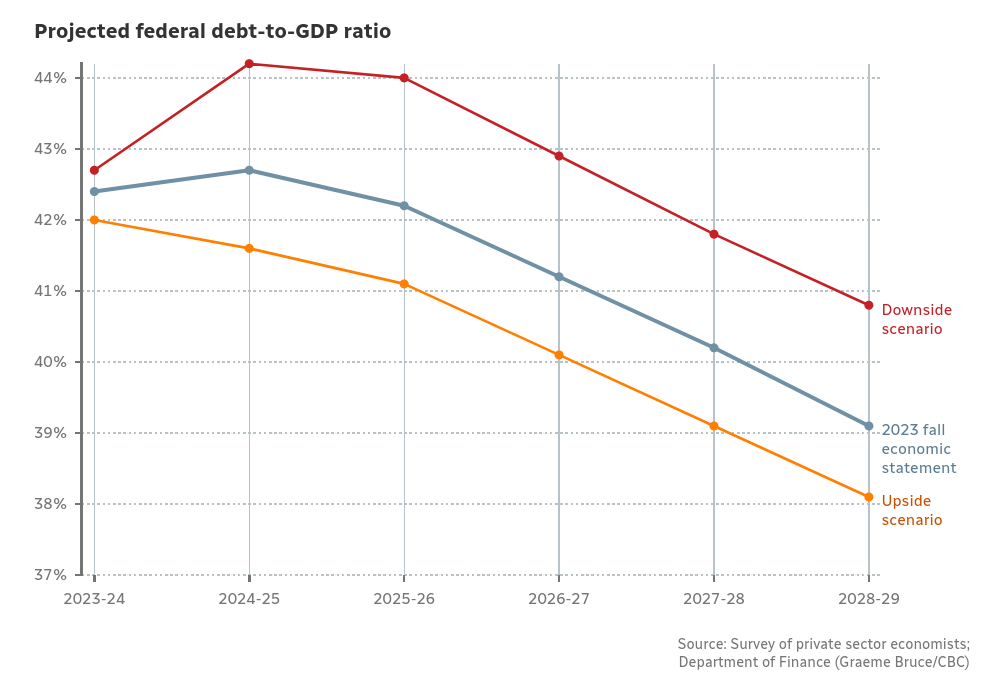

Canada debt to GDP

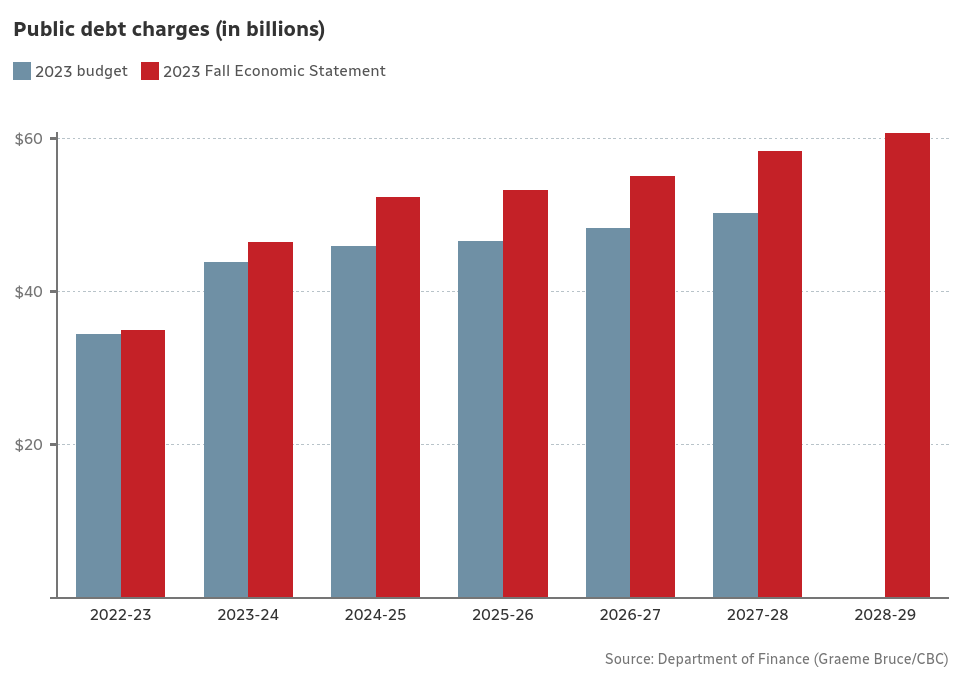

Canada's spending on debt payments

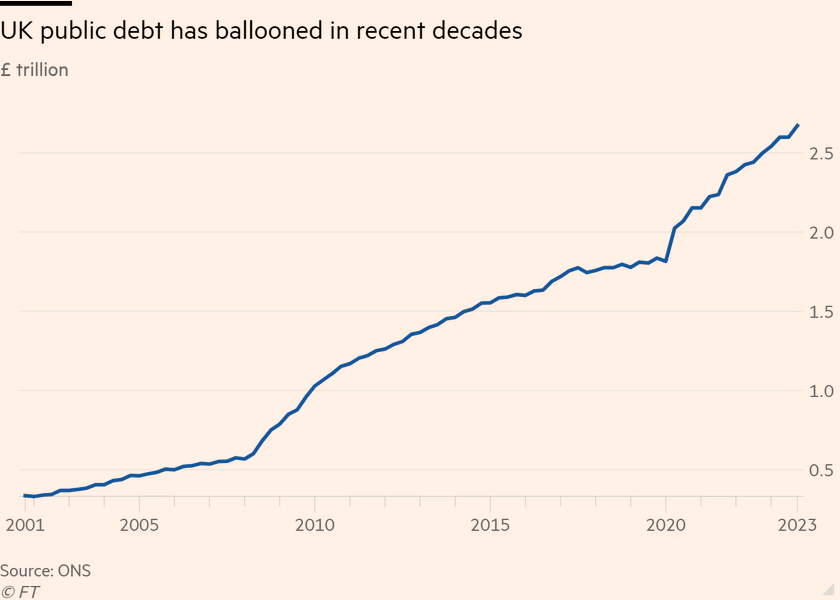

UK Debt:

Such big numbers!

The numbers are large and for more than a few reasons:

- inflation means things are more expensive and money is worth less than it was a few years ago, so the total needed to borrow to do the same thing is more

- the underspending on infrastructure and care over the previous 40 years is starting to catch-up with us and reality is asserting itself

- wars in Ukraine and so-called "geopolitical risk" is up, so spending on defence is up

- the world increases in complexity every year and in spite of our best efforts, that complexity increases costs

- current demographic trends has reduced per-person output in China and the West and increased real care costs

- climate change response takes a lot of money

- the USA went on a (narrative of a) spending binged and everyone else was forced to follow.

Where is all this hand-wringing about public debt coming from?

The world's largest economic meeting (ASSA) is happening right now. It brings together all the big names of orthodoxy (and some small names in heterodox economics) so they can all complain they do not know what is going on and issue dire predictions.

One dire prediction from the ASSA is that debt is too high. While it is the same voices issuing the same thing as before, conservative politicians use this to bang a drum and issue press releases.

Should we care? Yes. And, for two reasons.

- In the neoclassical world, we lend to private markets. This means that if politicians do not understand how the bond market will respond, things could become a little difficult. You only have to look at what happened to Liz Truss in the UK to know how true this is. Debt is a slow moving monolith until it isn't and then things can go sideways quickly.

- The focus on debt is a narrative tool of one side of the political spectrum. Conservatives are always talking about how much debt the government is in as if it is some anchor holding down the economy. Of course, they are talking about debt caused by supporting people and not debt supporting corporate profits. And, it has historically been quite a powerful narrative tool.

The focus on public debt is an extremely one-sided story. We must make sure that we are aware of the private market response to issuing debt, but the "size" of the debt is meaningless without talking about what it is being spent on.

It is also a kind of pendulum.

Higher debt now is simply part of the neoliberal period where we moved away from using direct profit subsidies as the main way to support capital and moved to artificially low borrowing rates.

That ended with central bank interest hitting zero (and even going "negative").

The response to the pandemic crisis was then to borrow to spend money without concern of whether there was value created.

The size of this profit subsidy in the lead-up to the pandemic meant there was little room to respond to that crisis without that new money risking inflation.

And, it did cause inflation because instead of that money being put to productive use creating value, it flowed into financial assets, replacing the low interest rate profit subsidy mechanism.

After the pandemic, we are in a situation where there is government spending both holding up those profits and attempting to deal with the tidal wave of historical deficits in the form of aging physical and social infrastructure.

It is a perfect storm of spending requirements. This means that even if some of those investments are going to result in value creation, it is not going to be value that will come for a few years at least.

The result is high debt. Someone has to borrow the money and capital isn't interested in doing that and consumers are already fully tapped, so it is going to be government borrowing.

There really isn't any way around this if we want to sustain our spending. And, even if we disagree on what that spending should be on, there is little disagreement that we are going to have to spend this money responding to all the issues above.

Now, this doesn't mean high debt is not something we need to focus on and have an answer to. We need to spend money on the correct things and spend less of it on profit subsidies and we need to increase taxes to pay for it.

How we have this conversation is going to depend on if the left can insert itself into the debate in a better way than we have in the previous 40 years.

What and how we spend must be part of the narrative because it will impact whether that increased debt load results in increased productivity and increased general wealth (to tax) or simply more wealth and income inequality.