February 12, 2024

Strikes

The right to strike is a fundamental component of free market capitalism for workers. Like the right to quit, the right to assemble to complain, and the right to go work for a competitor who pays more, they are all activities that must exist to sustain a competitive system where workers remove their individual labour. Sometimes they do it en masse, sometimes workers do it individually all at the same time. But, the right to withdraw your labour from this or that employer is fundamental.

These are rights in the fundamental case because of the stated and believed logic of competitive capitalism. Firms do not deserve to have workers, they must create a situation where workers want to exchange work for wages.

Of course, these are rights that are attacked and denied by capitalists who think that their right to seek profit (also a right under capitalism) does not stop at the seeking of that profit, but extends to achieving it. A right that expressly does not exist in form or function.

Like all "rights", these rights are in name only. They exist in real life only because people actively engage in these activities, and enough of the public support those action that we do not attempt to stop them.

The rights of workers to strike also exist because workers are sentient and have a minimum sense of worth. That means that taking the right away entirely usually ends poorly for employers as workers will walk of the job anyway.

The legal system exists for Capital to limit these rights in every way possible—this is capitalism, after all, and the system works for capital. But, even here we see some semblance of understanding that "what is good for capitalism generally" wins out over this or that employer demanding full slavery for their workers. (The affect of shifting degrees of workers' power and capital's notwithstanding.)

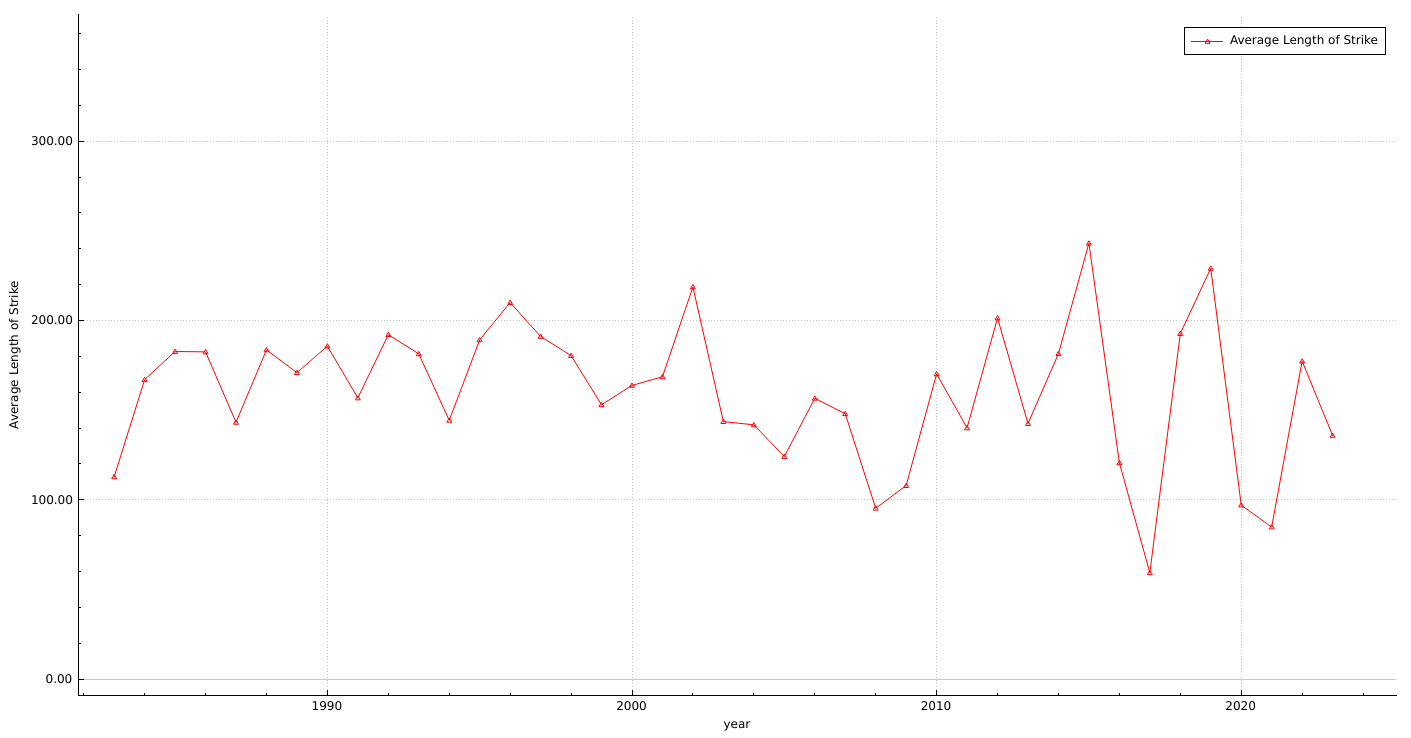

Why do we care about this? Lately, unionized workers have been exercising the right to strike a little more often than in the previous decade. (Though at a much reduced amount over the previous 30-40 years).

.png)

Increased strike activity is not surprising given the economic situation.

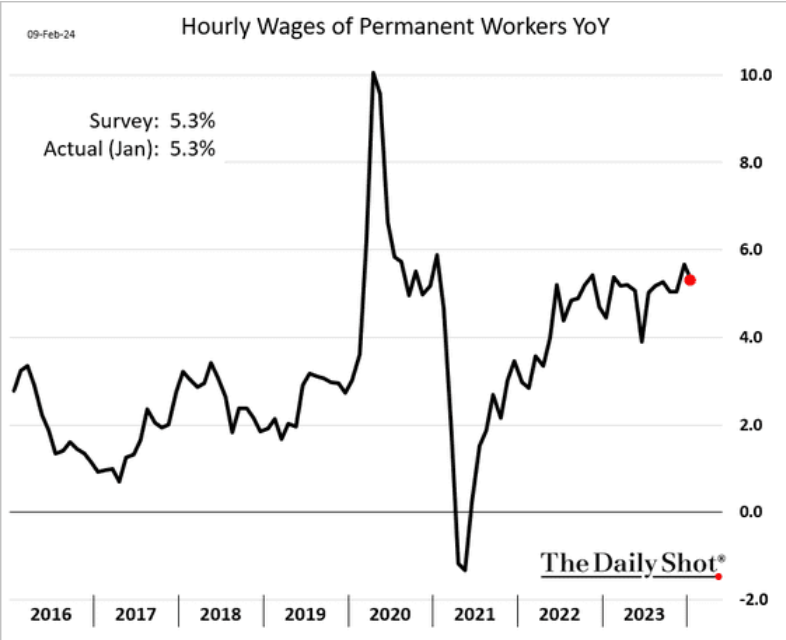

Strike activity follows broader economic shifts. Increased inflation is a big "broader economic shift" and unionized workers are demanding inflation adjusted wage increases at the table, confusing employers' who thought "2%" was the natural goal of wage growth irrespective of everything else.

Inflation has been declining since the late-1990s and many employers "forgot" that most negotiated wage deals are essentially attempts to get inflation adjustment deals. Declining inflation, declining percent increases in wages. Smaller numbers being fought over, fewer strikes over wages.

That doesn't mean that strikes don't happen when inflation is low, but they happen less often over wage growth. When inflation is 1.8% and the employer offers you 1.7%, are you really going to strike to get it to 2% when the cost of that strike eats up that difference? More than half the time, the answer is going to be "not worth it".

When inflation is high, however, and the difference is large between the cost of living increases experienced by working class unionized workers and the wage offer given by employers, the benefit of striking increases.

This is even more the case when non-union private sector workers are getting wage increases because the labour market is tight.

And, that's what we are seeing now. Employers essentially "forgot" that the wage gain average of about 1.6% since 2009 was so low because cost of living increases felt by workers was not significantly larger than that. Result: fewer strikes over wages previously, more strikes now.

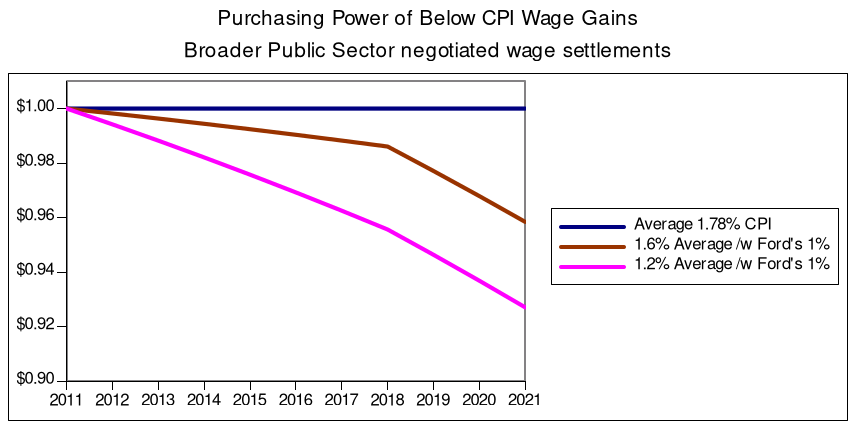

One last additional issue is that long periods of artificially low inflation create situations where pressure builds more slowly around wage growth, but will eventually lead to strike activity to make-up the difference.

Even before inflation became a headline, workers were going out on strike more often. The reason? Those 0.2% to 0.3% increases below cost of living increases—even when that inflation is small—start to add up. In the public sector, we saw very large gaps forming between what would have been inflation-adjusted wage increases and actual, experienced wages.

All the above has gotten us to where we were in 2023.

- A clear feeling of falling behind.

- Obvious "large" differences between needed wage gains and offers by employers.

- A noticeable increase in profit rates of employers (at the end of 2022).

- And, a general sense that a strike will not "cost more than gains made".

So, you get increased strike activity.

And, every time you get increased strike activity, you get increased understanding in the unions that the ability for employers to bring replacement workers in while workers strike undermines the point of the strike. Scabs undermine the right to strike, and workers rightly feel that is unfair, even under the logic of capitalism.

So, we have the push to eliminate ability of employers to deploy scabs.

Capital is unamused.

Public submissions to government on all topics from employer associations have all included demands for the state to not take away their strike-braking ability and to limit the right to strike of employees.

No where is this demand clearer than the transport sector.

Transport

_Work_Days_Lost_Number_of_Strikes_chartbuilder.png)

The expansion profits from off-shoring production to lower waged areas through global "free" trade meant that supply chain stability were pushed to their limit. These limits were surpassed in the aftermath of the pandemic and the increases in geopolitical conflict.

Supply chain disruptions played an out-sized roll in the cost of living increases since the pandemic. And, once unassailable transport companies became the focus of anger and frustration of suppliers and the part of the public that was paying attention.

The additional stress of these transport companies having to deal with their privileged position in society being undermined, workers in that sector have started to demand appropriate compensation and investment in health and safety.

Strike activity is up and calls by employer to eliminate the right to strike for the transport sector is at an all time high. Every submission over the previous year has called for the limiting of the right to strike.

Employers want to blame workers for what has been clearly a situation of under-investment leading to an undermining of supply chain resilience.

The thing is, that this up-tick in strike activity is only related to short-term issues right now. It would be nice if it was more than that, but it is just one data point (2023) that shows an uptick out of sync with the clear declining trend of strike activity in the sector over the previous 40 years.

We do not even see a change in the length of strike, so that calculus that is made on "cost of the strike" versus the "gain from striking" is still operating.

Indeed, we see no impact on the profit rates of these transport companies even after relatively protracted strikes.

We must be clear. The only reason that strikes have been up in 2023 is because cost of living increases were higher than "usual" since 2009 and employers tried to disconnect wage growth from that cost of living increase.

Where this will go is pretty obvious. Without intervention by unions to support strike action as a tactic to gain wage growth at the expense of profits a decline in strike activity over the next couple of years is inevitable.

We must put the focus back on these transport companies whose owners have benefited from attacks on labour and increased "importance" over the neoliberal period. The underinvestment in the system is clear and the increased number of incidents along our supply chain are a direct consequence of a declining regulatory environment and resulting low levels of investment.

The very minimum position is to support he right to strike and the right to strike effectively. This means supporting basic changes to the labour relations regime in Canada that bans replacement workers and links the right to strike with the fundamental aspects of competition in capitalism.

Employment

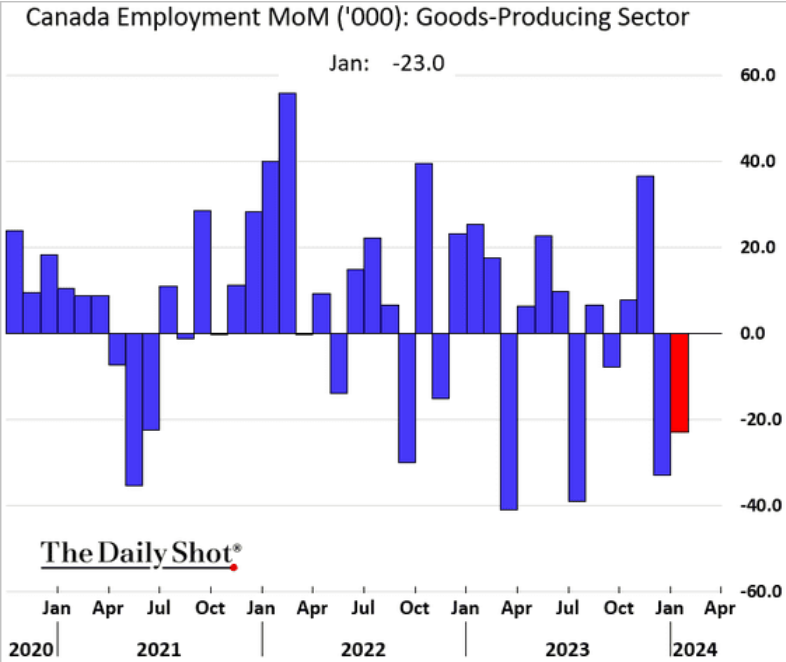

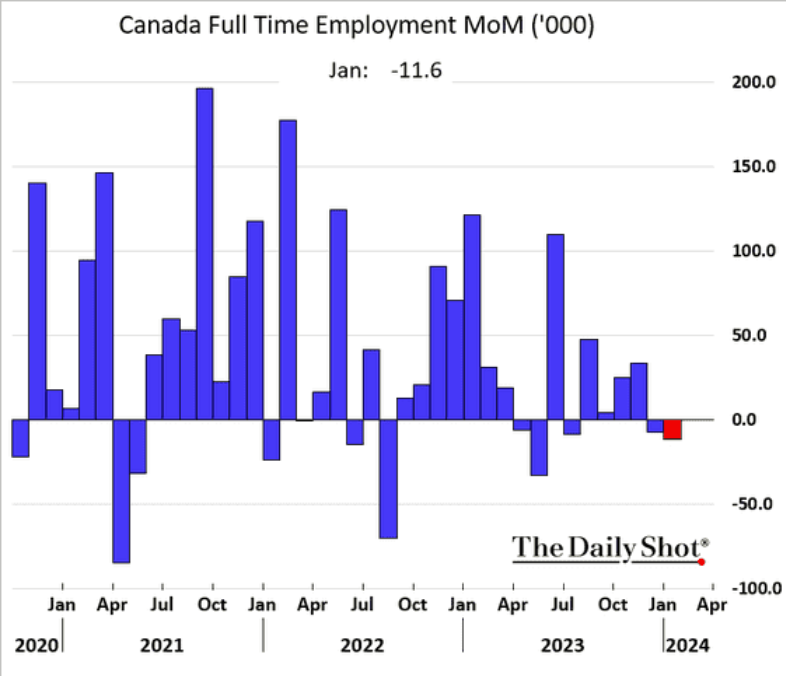

Some not so great employment numbers

What do we take from two measures of employment for January that look not so very good?

Unclear. Total employment is up, but we are in the middle of the layoff season. Seasonally adjusted employment data are not so clear that this is an unusual trend, but it is something to keep an eye on.

We will need to wait until we have some investment data to compare with this employment data to really get a sense of what is going on.