December 6, 2022

Complex supply chains and production costs

Many of the transitions in the European economy are being driven by the war in Ukraine and resulting sanctions against Russia and Russian-aligned companies. However, many of these transitions were going to happen anyway as a result of the economic push away from local production and use of oil and natural gas.

The problem with Europe and most of the rest of the world is that supply chains and production chains are tied-up in the subsidized use and production of these fossil fuels.

The head of the International Energy Agency has said that renewable energy will surpass coal in the next five years. While this is highly optimistic and more of a result of coal being replaced with natural gas, it does show it is resulting in a large shift in energy use. According to the IEA, the main obstacle to transition is, of course, geopolitics. The actual obstacle is the economics around this transition.

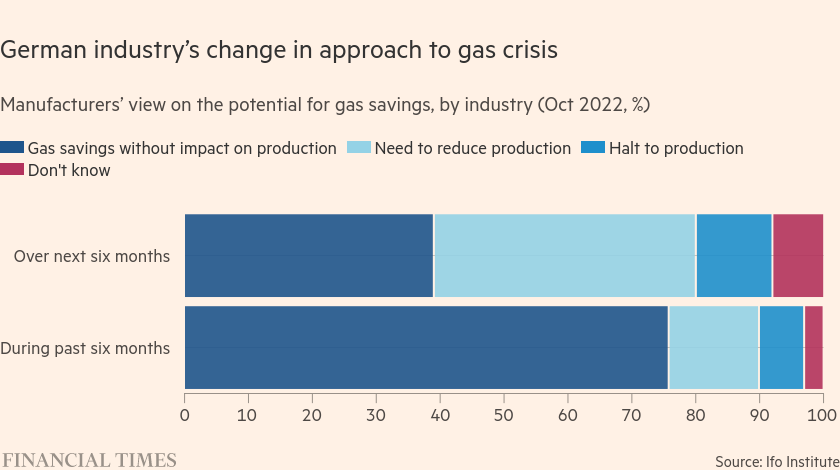

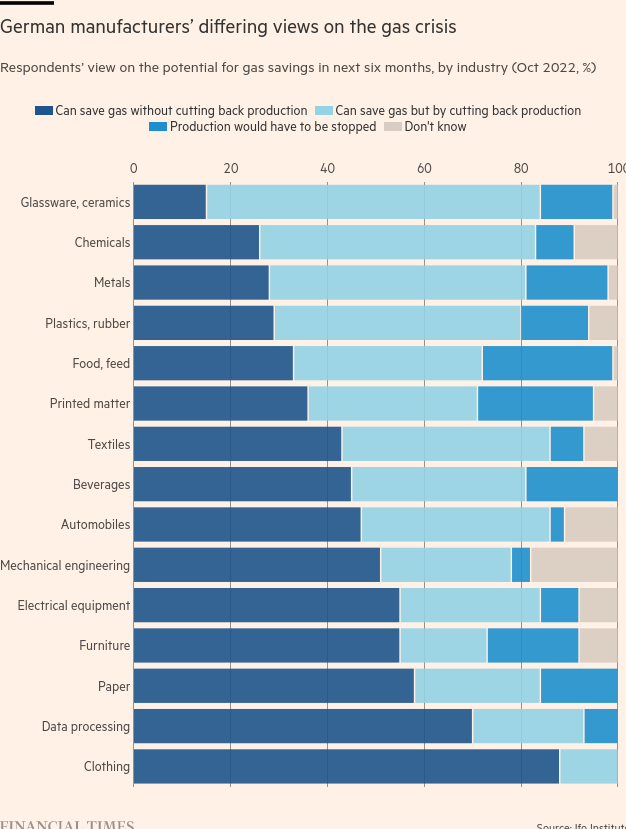

- High gas use industries account for 23 per cent of all industrial jobs in Germany, (and) had declined by 10 per cent since the start of the year.

- 1.5M workers could be affected

- BASF SA is permanently closing some chemical production in Germany (Europe) because of the price of natural gas. BASF mostly produces industrial inputs for other companies.

- The chemical industry in Germany employs 450,000 workers.

- Europe is importing ammonia for the firs time as it is cheaper elsewhere to make it.

- German and French production is directly affected by much of this shift away from cheap energy.

- Ceramics maker KPM does not have a solution to replace natural gas.

Europe has some processes for just transition for these workers, but has not had to use them at scale and the gutting of state supports is going to be felt.

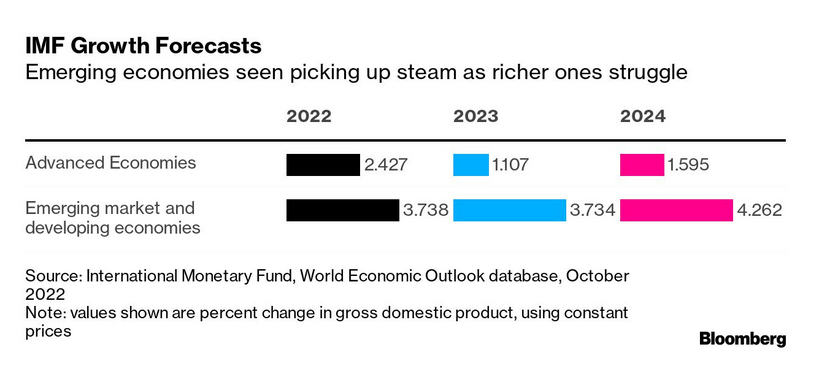

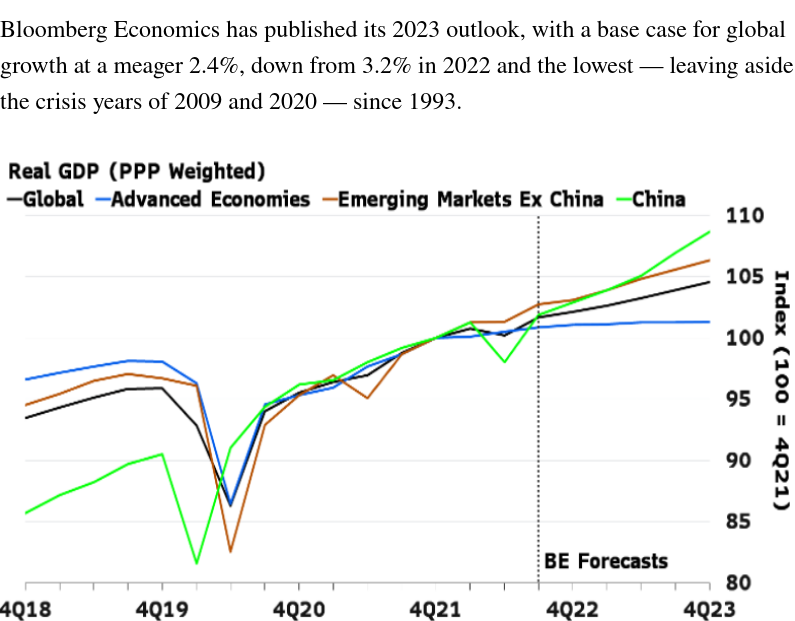

The previous 30 years have seen moves of production to China, India and other lower-cost (less stringent labour and environmental regulation) areas. The new cold war with China means some of that being brought back, but more likely it will mean shifting supply chains to other low-cost areas.

You can see this in the market estimates for growth in the near term:

The promise of localization of production is not as clearly realised as expected given that the private market still continue to drive productive investment decisions.

- Can local industrial production meet these new challenges when this local production was developed under a completely different trade and subsidy regime?

- What happens to production that needs these inputs to be produced? Is the result simply that the cheapest inputs are found elsewhere that do not have such stringent laws around production?

- If supply chains change to more local production, but offshore inputs, does that not result in a lot of upset for not a lot of climate gain?

Germany is changing its "industrial strategy" in response. Which is to say it is changing its industrial subsidy strategy.

“The German business model has to change,” Christian Lindner, the country’s finance minister, tells the Financial Times. “It was based on low energy prices . . . on an abundance of skilled workers, and open markets for Germany’s high-tech products.” But “this model doesn’t really work any more because many of the core elements have changed.” (FT)

A recent note by Deutsche Bank analyst Eric Heymann predicted the share of manufacturing in Germany’s gross value added — 20 per cent in 2021 — will decline in the coming years.(FT)

Should the state own the infrastructure that transports people?

The short answer is "yes" for many reasons. However, even Capital is getting this.

KLM, which owns air and rail transit, is now finding it easy to say that people should take the train since it owns both. It is a green washing exercise, but the logic is sound.

If the state owned the infrastructure for both, it could make the transition from carbon intensive transport like air and road to lower-carbon transport such as high-speed rail and public transit.

Many of these companies are state-supported and/or partially owned as it stands. The Dutch own 14% in AirFrance-KLM for nationalist reasons, but the outcome can be used for other reasons.

A full accounting of investment in alternatives to carbon intensive person transport is necessary. This transition of mass transport can happen much faster than the shift to personal battery-operated transport options—batteries are not included in many of these personal transport options as the lithium and other metals are still in the ground.

Electricity distribution systems are being modified—slowly—to support the individualized transport options. However, the public transport system is mostly already partially built. Expanding rail is possible in relatively short time-frames.

Flying is very convenient, but we have to face the likely future that it is likely going to be too expensive (under a full accounting) to continue as it exists now. Battery powered planes or giant air ships are not a realistic solution and belong in the same category as Carbon Capture and Storage: a delay tactic that will lead to climate catastrophe.

Freight is a different thing entirely. Subsidizing the profits of rail companies (as the Biden Administration just did by imposing a tentative "agreement") is not the answer.

As was told to me by some rail workers a few weeks ago, "these companies are not transport companies, they are profit printing machines". The reality is that if we want to bring down costs of freight, and it is likely we do, then we need strict regulation of transport routes while investing in newer higher-speed personal transport options.