April 22, 2024

Global growth, the IMF, and industrial policies

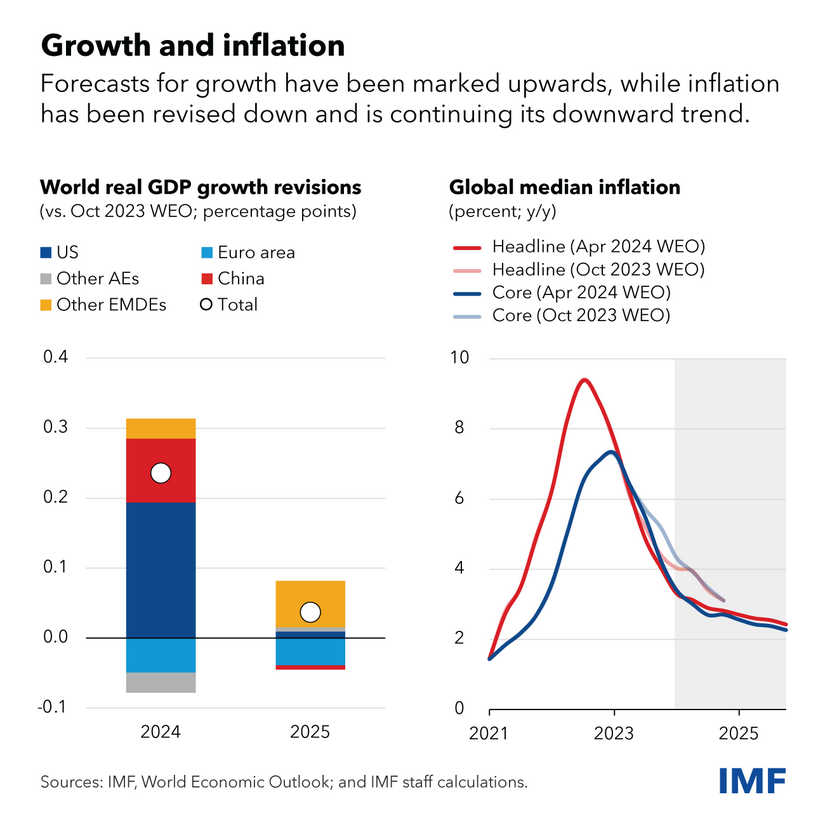

The IMF has adjusted its growth measure for the globe and the USA up.

The baseline forecast is for the world economy to continue growing at 3.2 percent during 2024 and 2025, at the same pace as in 2023.

Bloomberg Economics has 2024 world growth at 2.9% and 2025 year at 3.1%.

This is after it complained governments—especially the USA—were spending too much money, that there was too much inequality, and inflation is too high.

Calling the USA economy "overheated" and its long-term fiscal sustainability a "concern", it reluctantly pointed to its productivity and employment growth as a positive.

Everywhere else is having trouble except for the large "emerging markets" because of anti-China trade policies.

None the less, the IMF is calling for massive fiscal adjustments that would destroy most economies, pointing to the consolidations that happened in the USA in 1993 as a path to emulate.

That was the neoliberal "consolidation", decidedly not the path folks want to go down again.

I cannot say anyone is surprised by the IMF's position. It is the global neoliberal functionary. What is interesting is that no one, except maybe Canada's liberals, are listening to their terrible advice.

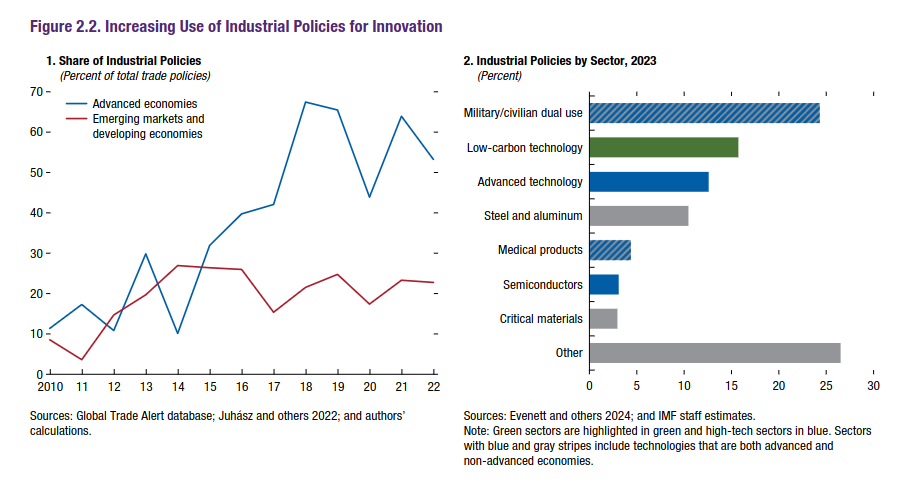

The report did have some interesting graphs on the use of industrial policies, especially in the more capitalist economies.

The IMF thinks industrial policies can be good only if there is specific commercialization that happens from those investments.

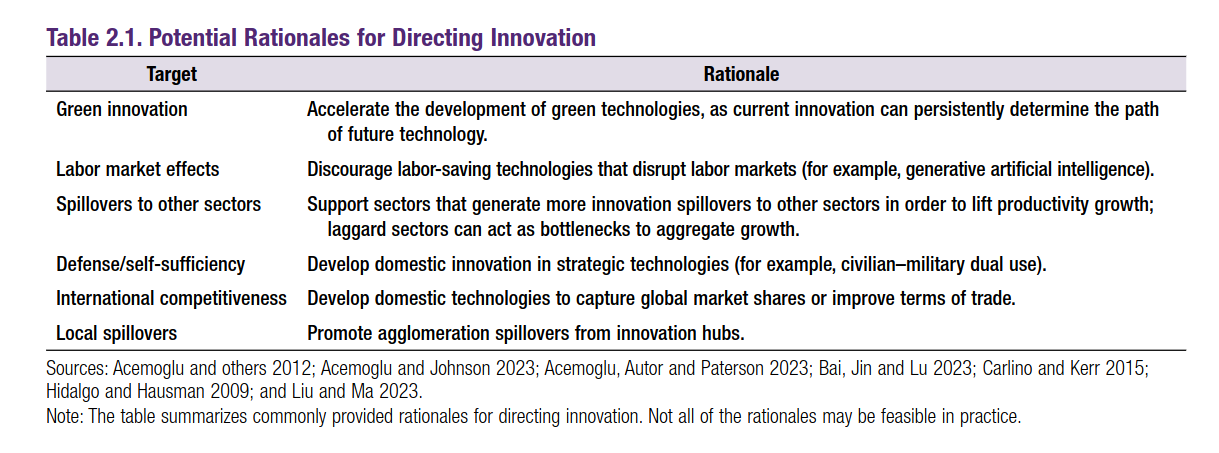

In sum, industrial policy for innovation can only be beneficial if the following conditions hold:

- Externalities can be correctly identified and precisely measured (for example, carbon emissions).

- Domestic knowledge spillovers from innovation in targeted sectors are strong.

- Government capacity is high enough to prevent misallocation (for example, to politically connected sectors).

- Policies do not discriminate against foreign firms, so as to avoid triggering retaliation by trade partners.

These would seems obvious to anyone, but are very specific. There is no difference between a climate industrial policy that spurs investment and an industrial policy in mining that spurs investment.

The policy frame is all the outcome of the IMF's economic modelling, which is based on rather strange assumptions most of the time.

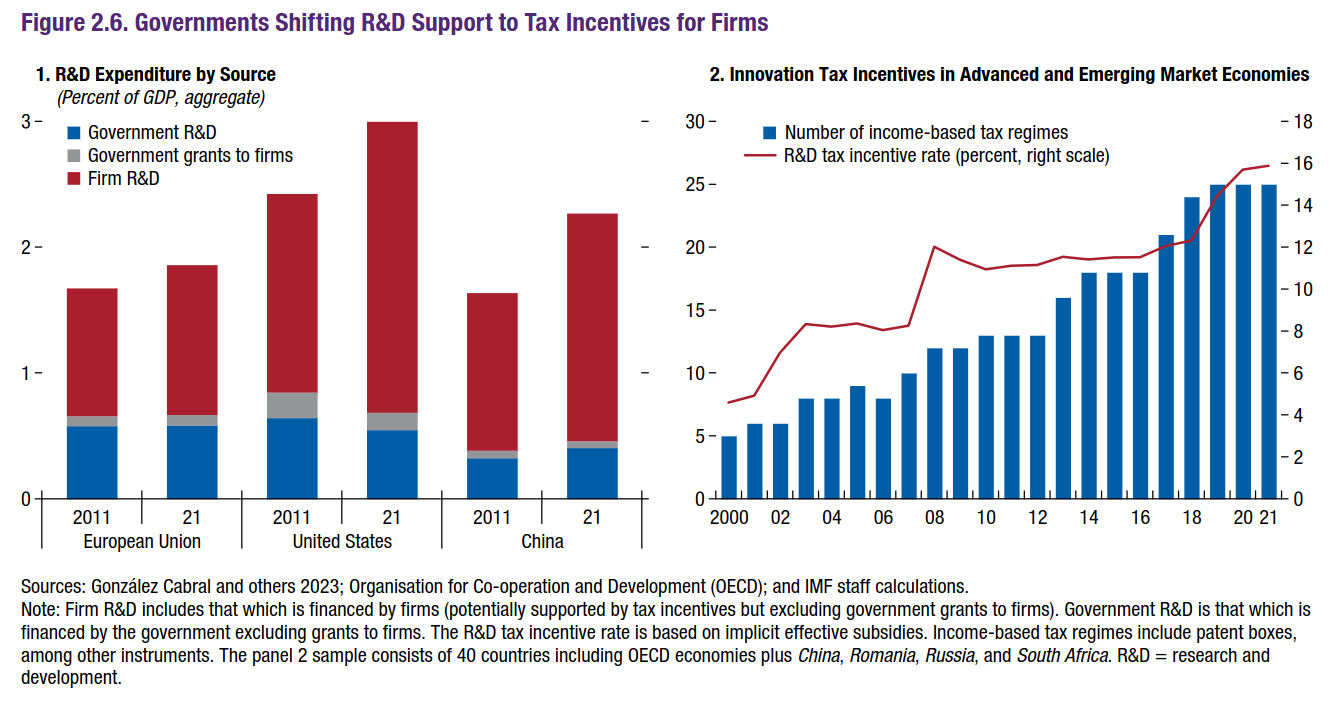

Industrial policies in this model are mostly based on state R&D supports which follws with the paper we reported on earlier in the year that showed huge benefits from state-supported industrial research spending.

The take-away is that even the IMF has had to admit that industrial policies are not all bad always.

However, governments are doing it wrong. They are relying on tax incentives for private-sector research and development investment. This is not working, but it is very expensive. And, all the money is going to R&D is in the Tech sector, which leaves the rest of the sector to simply buy the new Tech sector tech.

Interestingly, the IMF points to the Airbus/Boeing rivalry as an example of good uses of industrial policy, which used subsidized loans, and later reimbursable advances linked to sales. The result was to spread private risk-taking in innovation with government. This is the entire point of an industrial policy.

EU research and industrial support for Airbus beat Boeing for innovation implementation, and thus profit rate which lead to massive profit subsidies from the USA for Boeing to maintain itself.

The USA profit subsidy at this point did not result in increased innovation, simply profit subsidies enough to keep Boeing profitable for investors and thus in business.

The take-away: better to fund the innovation side of things.